The Oldest Plesiosaur in Town – Rhaeticosaurus mertensi

The fossilised remains of the world’s oldest plesiosaur described to date are reported in the journal “Science Advances”. The animal has been named Rhaeticosaurus mertensi.

Following the end-Permian mass extinction event, the world’s ecosystems took several million years to recover. In marine environments, just as on land, the mass extinction event led to devastating losses, it has been estimated that 57% of marine families died out. However, as the Triassic progressed, a number of terrestrial reptiles adapted to marine habitats and new, diverse ecosystems evolved.

It had long been suspected that the Plesiosauria (the long-necked plesiosaurs and the big-headed pliosaurs), the most diverse and longest-lived of all the extinct marine reptile groups, had their origins in the Triassic, but the fossil evidence for basal plesiosaurs was somewhat lacking. However, the discovery of a partially articulated fossil in a clay pit, close to the village of Bonenburg in North Rhine-Westphalia (Germany), has helped to plug a gap in the fossil record.

The Fossilised Remains of the World’s Oldest Plesiosaur

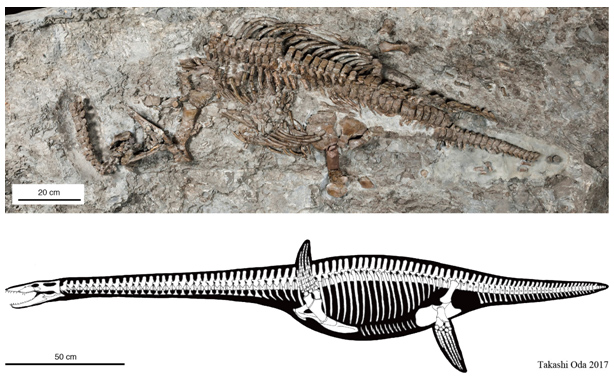

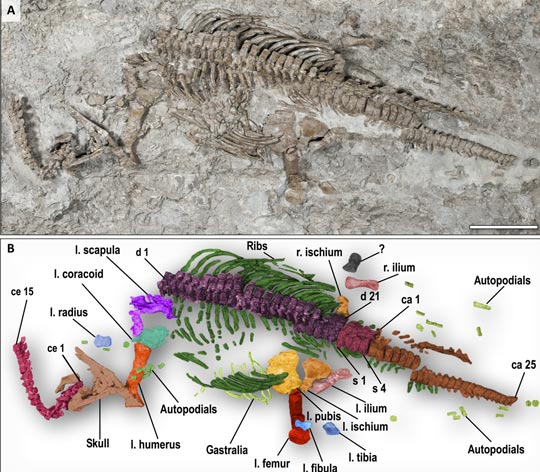

Rhaeticosaurus fossil (A) with line drawing (B).

Picture credit: Georg Oleschinski

Rhaeticosaurus mertensi

The fossil discovery marks the first plesiosaur specimen to be recovered from Triassic-aged rocks. It is the oldest plesiosaur to be found to date, the only one which dates from the Triassic Period.

Intriguingly, a study of cross-sections of some of the larger fossilised bones in the 2.37-metre-long skeleton, support previous research that suggests these marine reptiles grew rapidly and were (most likely), warm-blooded. The new species has been named Rhaeticosaurus mertensi, (ree-ti-co-sore-us mur-ten-see), the genus name comes from the last faunal stage of the Triassic (the Rhaetian), the trivial name honours private collector Michael Mertens, who made the initial fossil discovery.

201-million-year-old Fossil

Michael Mertens discovered the specimen in 2013, some of the neck bones had been lost but the majority of the skeleton was in situ. The resulting excavation, study and publication in the academic journal “Science Advances”, is a credit to the parties involved, namely Herr Mertens, the natural heritage protection agency, the Münster museum, and scientists from various institutes including Bonn University, the Osaka Museum of Natural History, the University of Tokyo and the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, amongst others.

Co-author of the Scientific Paper Tanja Wintrich with the Fossil Finder Michael Mertens

PhD student Tanja Wintrich with Michael Mertens show where the fossil was found.

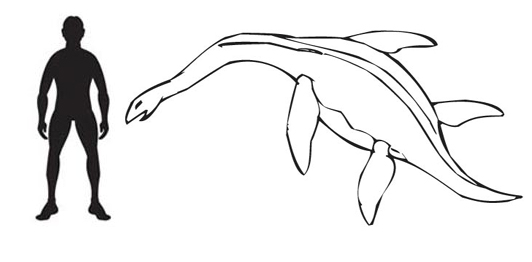

An Illustration of a Typical Long-necked Plesiosaur

Bone Histology Suggests Rapid Growth and Potential Endothermy

The Triassic plesiosaur already has the typical long-necked plesiosaur bauplan and it was, like most of its descendants, a pelagic piscivore (an active swimmer, hunting fish). Analysis of the bone structure indicates that the specimen represents a juvenile, one that was growing rapidly. Thin cross-sections of fossil bone were compared to Jurassic and Cretaceous specimens and the team’s findings support the hypothesis that to grow this quickly, these reptiles needed to be warm-blooded.

Professor Sander stated:

“Plesiosaurs apparently grew extremely fast before reaching maturity. Since plesiosaurs spread quickly all over the world, they must have been able to regulate their body temperature to be able to invade cooler parts of the ocean.”

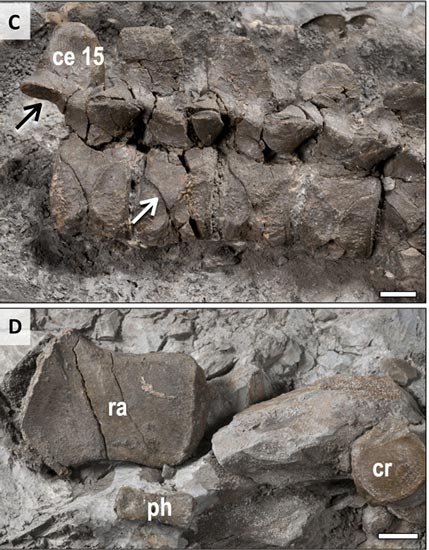

The Hind Leg Bones of Rhaeticosaurus mertensi

Left femur (f), tibia (ti) and fibula (fi). The proximal femur is a cast because the original was sectioned for histology (scale bar = 1 cm).

Articulated Cervical Vertebrae (C) and Elements from the Left Front Limb (D)

Cervical vertebrae (C) and the left radius (ra), a phalanx (ph) and a (cr) carpal element (D).

The scientific paper: “A Triassic Plesiosaurian Skeleton and Bone Histology Inform on Evolution of a Unique Body Plan” by Tanja Wintrich, Shoji Hayashi, Alexandra Houssaye, Yasuhisa Nakajima and P. Martin Sander published in the journal “Science Advances”.