Fossil hunters have uncovered the remains of an ancient marine ecosystem that arose in the aftermath of the most devastating mass extinction in Earth’s history.

The spectacular haul of 20,000 fossils from a hillside in southwestern China represents the first discovery of a complete ecosystem which bounced back after life was nearly wiped off the face of the planet 252m years ago.

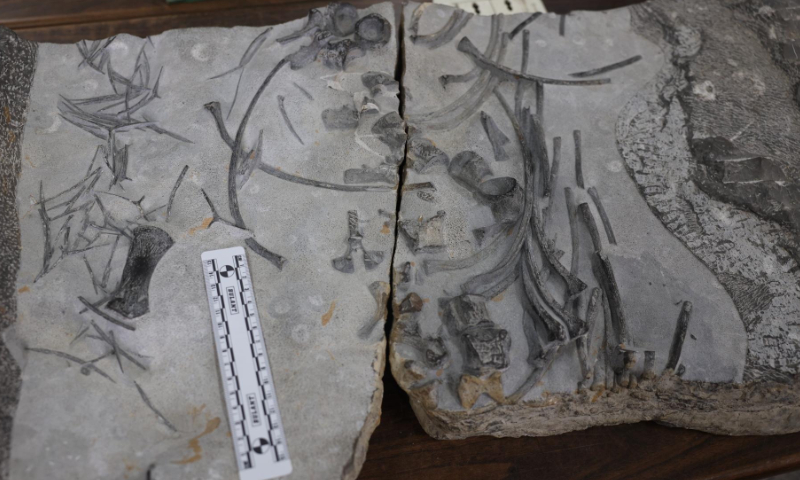

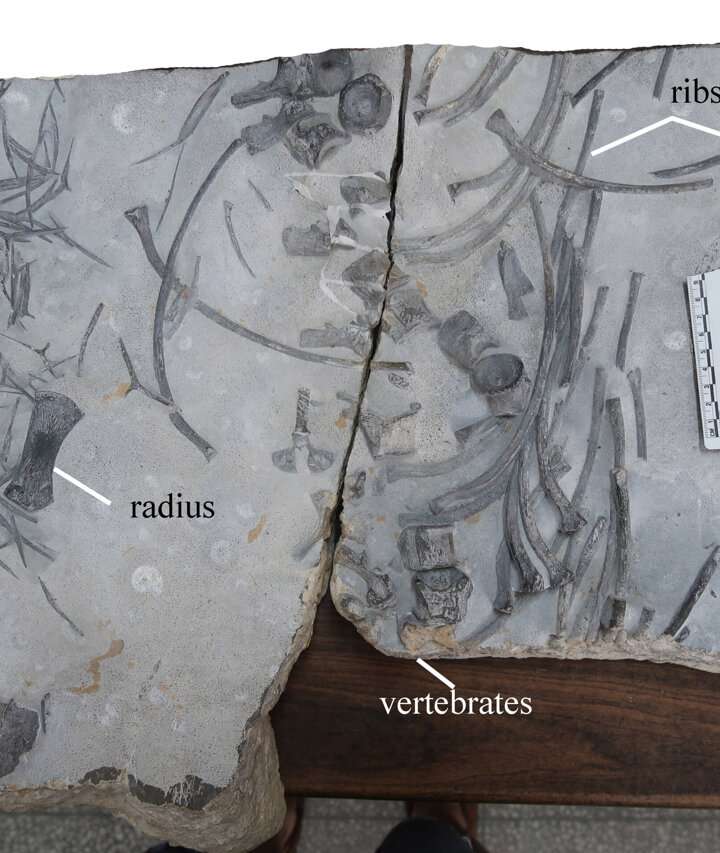

The beautifully preserved remains include molluscs, sea urchins and arthropods, alongside much larger animals that occupied the top of the food chain, such as carnivorous fish and the first icthyosaurs, predatory marine reptiles that grew to four metres long.

Among the remnants are rare fragments of land life that survived the same period, including part of a conifer plant and the tooth of an archosaur reptile.

The fossils were excavated from rocks that formed when ocean sediments settled out and solidified many millions of years ago in what is now Luoping county in the Yunnan Province of China.

The Earth has witnessed several mass extinctions in its 4.5bn year history, but the event that struck at the end of the Permian was unequaled in scale. Some 96% of marine species and 70% of land vertebrates were lost in what has been called “the great dying”.

![A new basal ichthyosauromorph from the Lower Triassic (Olenekian) of Zhebao, Guangxi Autonomous Region, South China [PeerJ]](https://dfzljdn9uc3pi.cloudfront.net/2022/13209/1/fig-3-1x.jpg)

What caused such global havoc is still open to debate, but Michael Benton, a paleontologist at Bristol University who led the latest research, said evidence points to prolonged and violent eruptions from the Siberian traps, a huge region of volcanic rock. In this scenario, mass eruptions triggered environmental catastrophe by belching an overwhelming quantity of gas into the atmosphere for half a million years.

“The main follow on was a flash warming of the Earth. That caused stagnation in the oceans, as normal circulation shut down. On land, the consequence of all the carbon dioxide and other gases appears to have been massive acid rain that killed the forests and stripped the landscape bare,” Benton said. “This was the greatest of all mass extinctions, the time when life was most nearly completely wiped out.”

What life survived became the starting point for a recovery that played out over the next ten million years. Some of these organisms, known as “disaster species” clung on through sheer hardiness, somehow coping with the harsh conditions of scarce food, wild variations in temperature and little oxygen in the oceans.

![A new basal ichthyosauromorph from the Lower Triassic (Olenekian) of Zhebao, Guangxi Autonomous Region, South China [PeerJ]](https://dfzljdn9uc3pi.cloudfront.net/2022/13209/1/fig-5-full.png)

By studying the fossils, Benton and his colleagues at the Chengdu Institute of Geology and Mineral Resources and the University of Western Australia, hope to piece together how life can come back from the brink. “The recovery from mass extinction touches on current concerns about biodiversity and conservation. Why do certain species go extinct? Which species come back? How do you rebuild an ecosystem and how long does it take?” said Benton. The study appears in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

The Luoping fossils show that many small organisms at the bottom of the food chain came back within two to three million years. Once their populations stabilised, other creatures that could feed on them recovered, including molluscs and shellfish. The familiar spiralled ammonites bounced back surprisingly fast. Only later did the larger predators reappear in the oceans.

The loss of so many species at the end of the Permian gave new creatures the chance to take their place. Before the mass extinction, the top ocean predators were primitive sharks. Some survived and recovered, but they were joined by the first predatory icthyosaurs. “Part of it is a rebuilding of the ecosystem from the grim survivors, but there are also opportunities for new groups. There were essentially no marine reptiles before the extinction, but this gave them a way in,” said Benton.

Paleontologists have unearthed other fossils that give a glimpse of life coming back from the Permian extinction, but the extensive remains at Luoping are unique in having the rich biodiversity of a fully functioning ecosystem, from the lowliest plankton to carnivorous apex predators.