For the first time, scientists discovered a powerful ‘black hole wind’ that blew through a nearby galaxy for hundreds of days, crushing star formation and reshaping the galaxy. Something similar may already have happened in the Milky Way.

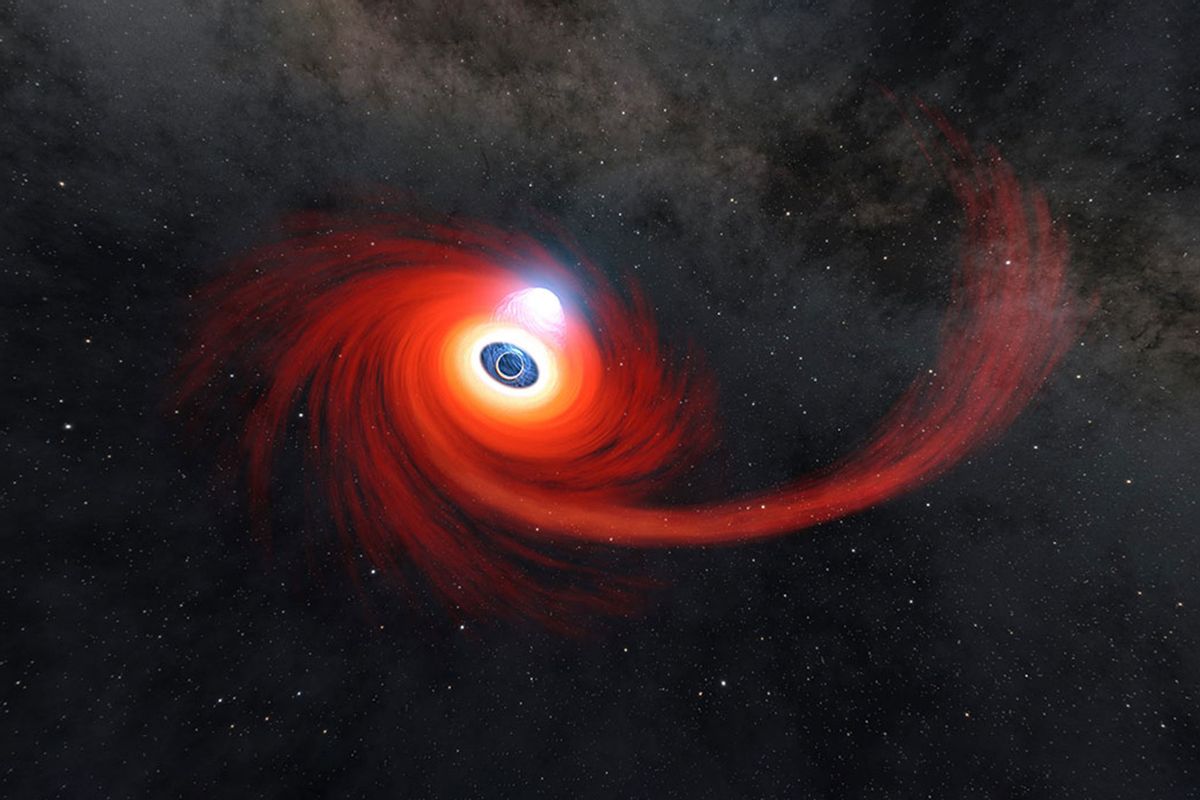

An illustration of ultrafast wind gushing out of a supermassive black hole (Image credit: ESA)

A temperamental black hole is helping scientists learn more about how galaxies evolve. In a new study published Feb. 1 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, researchers describe how an outburst from a distant black hole changed its galactic landscape — and how similar activity may have shaped our own galaxy.

Markarian 817 is a spiral galaxy located some 430 million light-years from Earth. Like our galaxy, the Milky Way, it has a massive black hole at its center. Such objects help hold galaxies together, exerting enough gravity on stars, dust and other material to keep everything slowly orbiting around a central point — and occasionally gobbling up some of that matter when it falls too close to the black hole’s event horizon. But recently, researchers spotted Markarian 817’s black hole doing something unexpected.

Rather than steadily consuming the gas and dust around it, the black hole experienced a “temper tantrum” and suddenly flung the matter away. This produced a bald patch in the galaxy in which very few new stars could form. The observation “suggests that black holes may reshape their host galaxies much more than previously thought,” Elias Kammoun, an astronomer at the Roma Tre University in Italy and co-author of the study, said in a statement.

Kammoun and his team began their study with data from NASA’s Swift Observatory, which detects light in the X-ray, ultraviolet and gamma-ray spectra. When the researchers noticed a significant dip in the amount of X-ray light coming from Markarian 817, they decided to take a closer look. This time, they used data from the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton mission, an extremely sensitive X-ray space observatory designed to study galaxy formation.

XMM-Newton enabled the team to get to the bottom of the emissions dip. As it turns out, the culprit was a sustained gust of ultrafast cosmic wind whipping around the galaxy’s black hole at several percent of the speed of light, obscuring the X-ray light of the galaxy. While it’s fairly normal for black holes to send out brief “puffs” of gas, such a prolonged storm — which lasted several hundred days — had not been observed before, the researchers said.

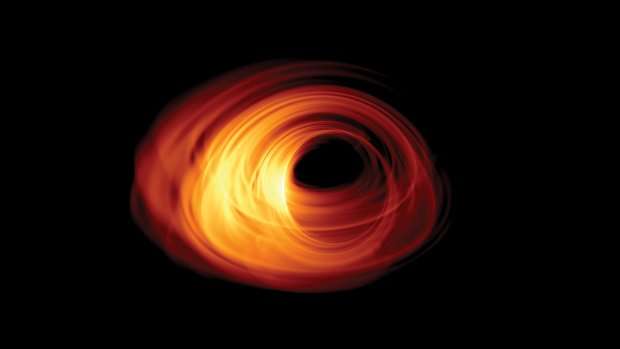

An image of Sag A*, the supermassive black hole at the heart of the Milky Way, taken with the Event Horizon Telescope. (Image credit: EHT Collaboration)

When the dust finally settled, the team saw that the region of Markarian 817 immediately around its black hole had been largely cleared of dust. This helps unlock a key part of the process of galaxy formation — namely, that black holes can kill star formation in wide swaths of the galaxies they inhabit, changing the shape of those galaxies. According to the researchers, this finding could even explain the peculiar bald patch surrounding our own galaxy’s supermassive black hole, Sagittarius A*.

“This highlights the prime importance of the XMM-Newton mission for the future,” Norbert Schartel, a project scientist for XMM-Newton, said in the statement. “No other mission can deliver the combination of its high sensitivity and its ability to make long, uninterrupted observations.”