Is there lightning on Venus?

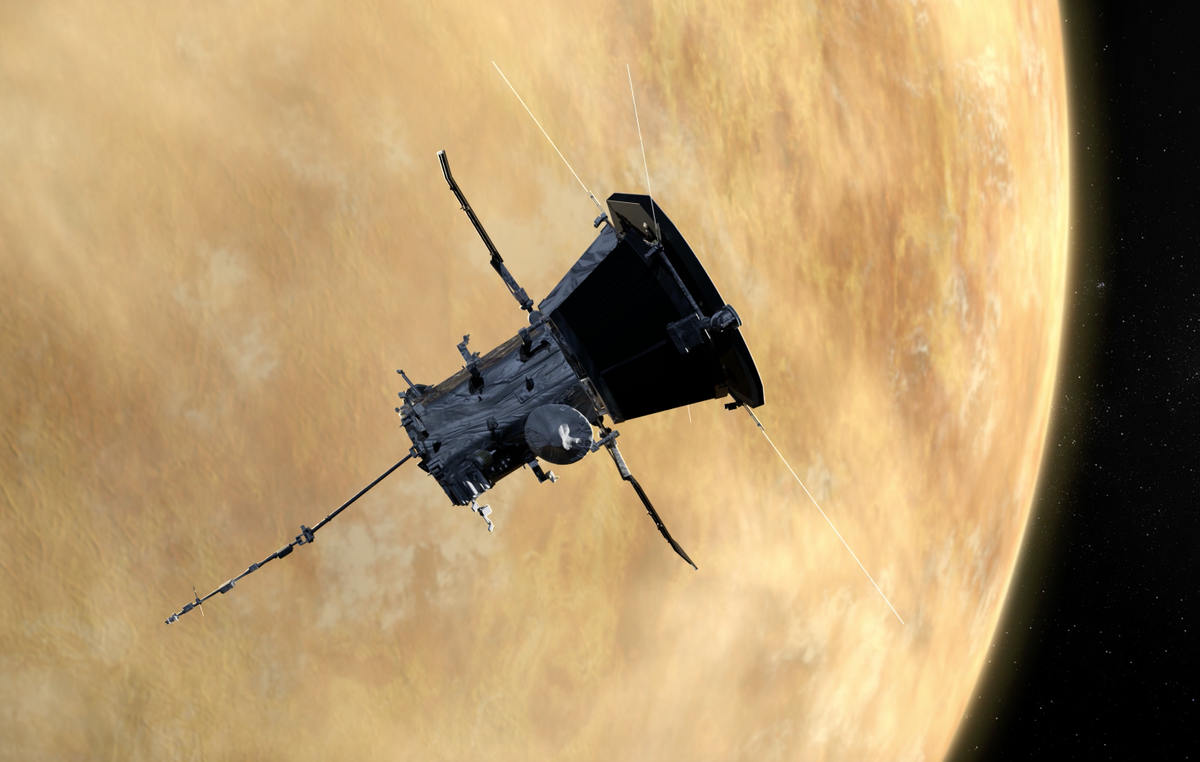

Is there lightning on Venus? Scientists have debated this question for decades. With its thick, cloudy atmosphere, we might expect Venus to have lightning, just as Earth does. Many artist’s concepts have depicted mighty lightning bolts crashing down under Venus’ heavy clouds. But now, a new study from researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder casts doubt on the idea of Venus lightning. The findings were announced on October 2, 2023. Interestingly, the insights come from data collected not by an earthly telescope or a Venus spacecraft, but by NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, first spacecraft to touch the sun. The new results suggest lightning is rare on Venus, if it happens at all.

%20-%201.jpeg)

Lead author Harriet George and her colleagues published their peer-reviewed paper in Geophysical Research Letters on September 29.

George said:

There’s been debate about lightning on Venus for close to 40 years. Hopefully, with our newly available data, we can help to reconcile that debate.

Parker Solar Probe provides another explanation

As its name implies, Parker Solar Probe is a sun-focused space mission. It’s been busily studying the sun since it launched in 2018. So how would it study Venus? It did so in February 2021, when it passed by the planet at a distance of only 1,500 miles (2,400 km). George and her colleagues used the PSP/FIELDS Experiment, a set of electric and magnetic field sensors on the spacecraft, to analyze the atmosphere.

During the flyby, Parker Solar Probe detected electromagnetic waves called whistler waves in Venus’ atmosphere. On Earth, lightning can cause these pulses of energy. But is the same true for Venus? Analysis of the data provided another plausible cause: disturbances in Venus’ weak magnetic field. More specifically, magnetic reconnection-in, a phenomenon where the twisting magnetic field lines that surround Venus come apart then snap back together. The effects can be explosive.

Analysis of the whistlers showed something unusual: they were moving downward instead of upward. Whistlers from lightning would be expected to move upward and out of the atmosphere. Co-author David Malaspina said:

They were heading backward from what everybody had been imagining for the last 40 years.

The new results also agree with a previous study from 2021. That study, led by Marc Pulupa of the University of California, Berkeley, did not detect any radio waves from lightning strikes as had been hoped for.

What are whistler waves?

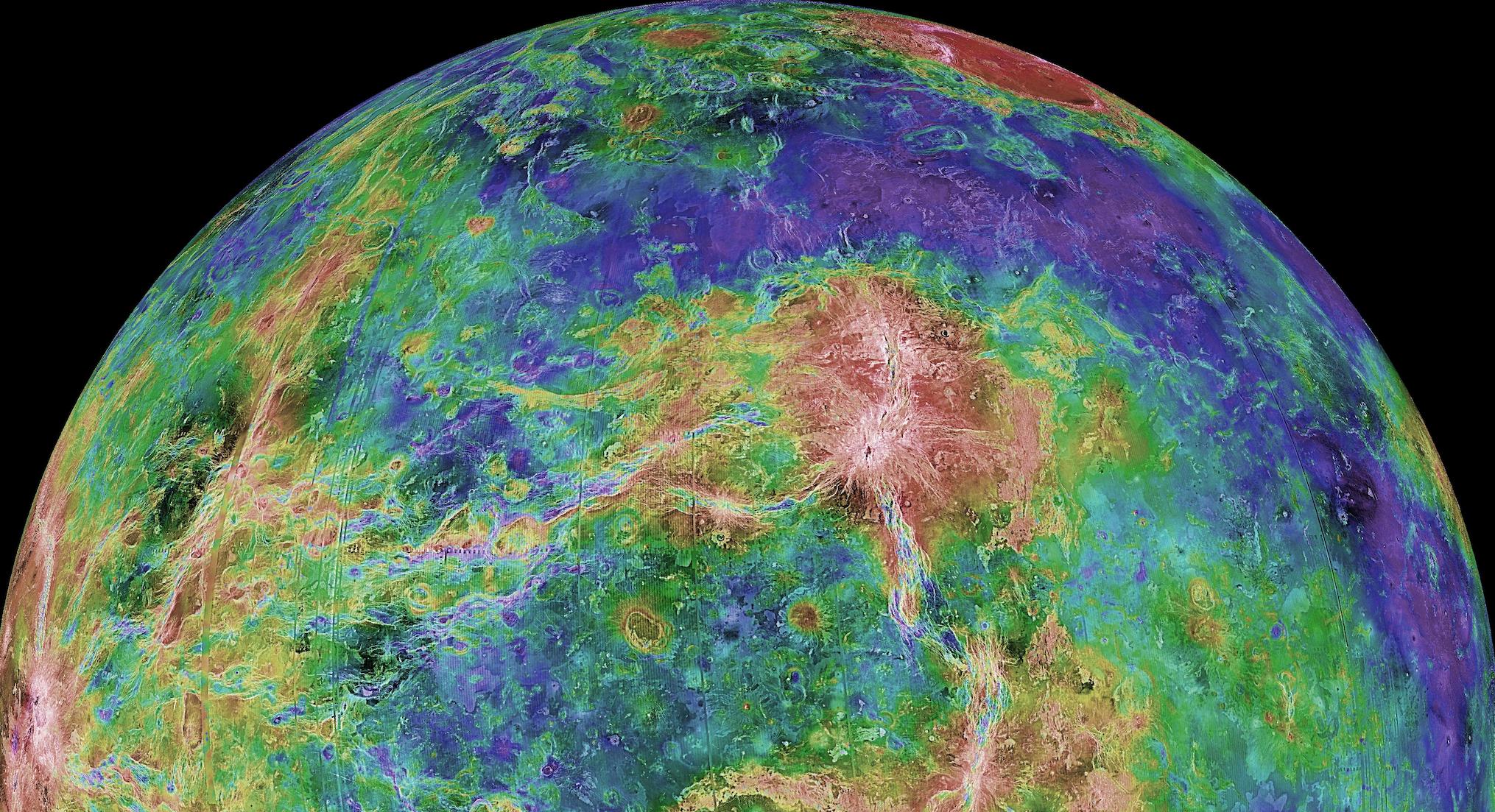

One of the primary reasons scientists suspected Venus might have lightning was the detection of whistler waves. NASA’s Pioneer Venus spacecraft first detected whistler waves back in 1978. The whistler waves were hundreds of miles above the ground, leading scientists to think that lightning may have caused them.

On Earth, light can disturb electrons in the atmosphere. The electrons, in turn, generate whistler waves. Those waves then travel up through the atmosphere and into space. George said:

Some scientists saw those signatures and said, ‘That could be lightning.’ Others have said, ‘Actually, it could be something else.’ There’s been back and forth about it for decades since.

Why are they called whistler waves? The answer, simply, is that they create audible whistling tones. Radar operators at the time could actually hear them in their headphones.

More data needed to confirm or refute lightning on Venus

Going by the number of whistler waves detected on Venus, if lightning did caused them, then that would mean there are about seven times more lightning strikes on Venus than on Earth.

Now, Parker Solar Probe, a mission not even designed to study Venus, may finally provide a conclusive answer. Its previous flyby of Venus wasn’t the only one. In fact, it will pass by the planet seven times altogether, and has already conducted five of those flybys.

Even though Parker Solar Probe isn’t a Venus mission, it has still provided valuable insights into the planet’s atmosphere and how it behaves. As Malaspina said:

Parker Solar Probe is a very capable spacecraft. Everywhere it goes, it finds something new.

The new results aren’t quite a full refutation of lightning existing on Venus. The researchers say they want to analyze more whistler wave data before finally ruling it out. Parker Solar Probe’s final flyby of Venus will be in November 2024. The spacecraft will skim the top of the atmosphere at only 250 miles (400 km) above the surface. That will be an excellent opportunity to gather the data needed.

Bottom line: Is there lightning on Venus? Contrary to previous belief, a new study from the University of Colorado Boulder suggests it is rare, if it even exists at all.