The dusty remains of a horse-sized tyrannosaur have shed light on an evolutionary mystery that eventually resulted in the most fearsome predators to walk the Earth, not to mention nightmares for countless four-year-olds.

While Tyrannosaurus rex topped the food chain 70m years ago, the earliest known tyrannosaurs were far less impressive beasts. Skeletons dating back 165m years reveal the ancestors of T rex were not much larger than a human. Quite how they rose to dominance has long been obscured by a 20m-year gap in the fossil record.

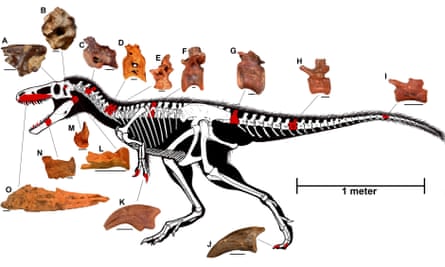

The discovery of a partial skull belonging to a 90m-year-old tyrannosaur has now given dinosaur hunters their best clue yet. While the animal was still small, at only 250kg and 3 metres long, its brain had evolved an impressive sensory system. The more advanced brain may have helped secure the tyrannosaurs’ rise to dominance.

Named Timurlengia euotica, the newly found species had an elongated inner ear, which would have made it good at hearing low frequency sounds: all the better for hunting prey. The name comes from Timur Leng (also known as Timur or Tamerlane), a 14th-century Central Asian warlord, and euotica, meaning “well-eared”, a reference to the animal’s large cochlea. Other parts of the skull are missing though, making it impossible to know how good its hearing and vision were.

The discovery suggests that T rex and its closest relatives did not develop their heightened senses after reaching gigantic proportions, but instead beefed up later on. Towards the end of the age of the dinosaurs, tyrannosaurs had evolved into species such as T rex, with adults that weighed 7 tonnes and measured 13m from snout to tail.

Bone parts of Timurlengia euotica Photograph: Todd Marshall/Steve Brusatte/Uni/PA

“This is the first and only one we have from this big gap in the fossil record, and it finally tells us what tyrannosaurs were doing as they transitioned into the huge T rex,” said Stephen Brusatte, a paleontologist at Edinburgh University, who describes the fossils in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“It gives us some insight into how T rex and its closest cousins became these giant, dominant, utterly successful apex predators. The tyrannosaurs evolved these features of the brain when they were still small, and those enhanced abilities may have come in handy when the tyrannosaurs had the opportunity to become dominant,” he added.

The dinosaur’s braincase was found lying on the ground in the Kyzylkum desert in northern Uzbekistan during a field expedition in 2004. Hans-Dieter Sues at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington DC said that while the team realised the skull belonged to a predatory dinosaur, they could not establish the species until they brought in Brusatte, who had studied tyrannosaurs in Mongolia and China. Timurlengia was a “nimble pursuit hunter” Sues said, with slender, blade-like teeth for slicing through meat.

Other bones found at the Uzbek site belonged to raptors, a smattering of primitive mammals, and flying reptiles called pterosaurs. Large plant-eating, duck-billed dinosaurs lived among them and likely constituted dinner for Timurlengia.

For millions of years, tyrannosaurs were second-tier predators, stalking their prey beneath the larger, more ferocious allosaurs and related beasts. But for reasons that are not clear, allosaurus and its predatory peers went extinct, leaving the top rung of the foodchain empty. No longer overshadowed by allosaurs and their kind, the tyrannosaurs took over. “In evolving some of these advanced sensory features and intelligence early on, the tyrannosaurs may have had the edge to fill that niche when the other predators died out,” said Brusatte.

While keen to stress that little can be learned from just one beast, Brusatte adds that one clue to the animal’s evolutionary past is better than none. If the animal was typical for tyrannosaurs of the time, it suggests brains came before brawn on the path to apex predator. “It seems to show that tyrannosaurs evolved their huge size really late in their history, right towards the end of the age of dinosaurs, and maybe quite suddenly.”

Roger Benson, a paleontologist at Oxford University, said the finding is convincing. “I don’t think it directly tells us whether enhanced hearing was a particularly important prerequisite for tyrannosauroids to become giant predators, but that’s an interesting hypothesis,” he added.