The tooth-marked bones of giant, plant-eating dinosaurs have provided a fascinating glimpse into the prehistoric feeding habits of large carnivores living in North America around 150 million years ago—an area one expert told Newsweek was “neglected.”

For a study published in the journal PeerJ Life & Environment, a team of researchers investigated bite marks left on the bones of enormous sauropod dinosaurs—such as Diplodocus and Brontosaurus—that were made by carnivorous theropod dinosaurs.

Sauropods are a group of dinosaurs that includes the largest land-dwelling animals ever to walk the Earth. These quadrupedal dinosaurs, which could grow to colossal sizes, are characterized by their very long necks, long tails, small heads and thick legs.

Theropods, meanwhile, are a hugely diverse group of dinosaurs that were primarily carnivorous and bipedal. Modern birds are descended from one lineage of small theropods, meaning they are also members of this group.

Bones with traces of bites—i.e. tooth marks—provide important evidence of the feeding choices and behaviors of long-extinct carnivorous animals.

In the case of dinosaurs, most bite traces that have been documented to date have been attributed to large Tyrannosaurs—a family of carnivorous theropods known primarily from fossils found in North America.

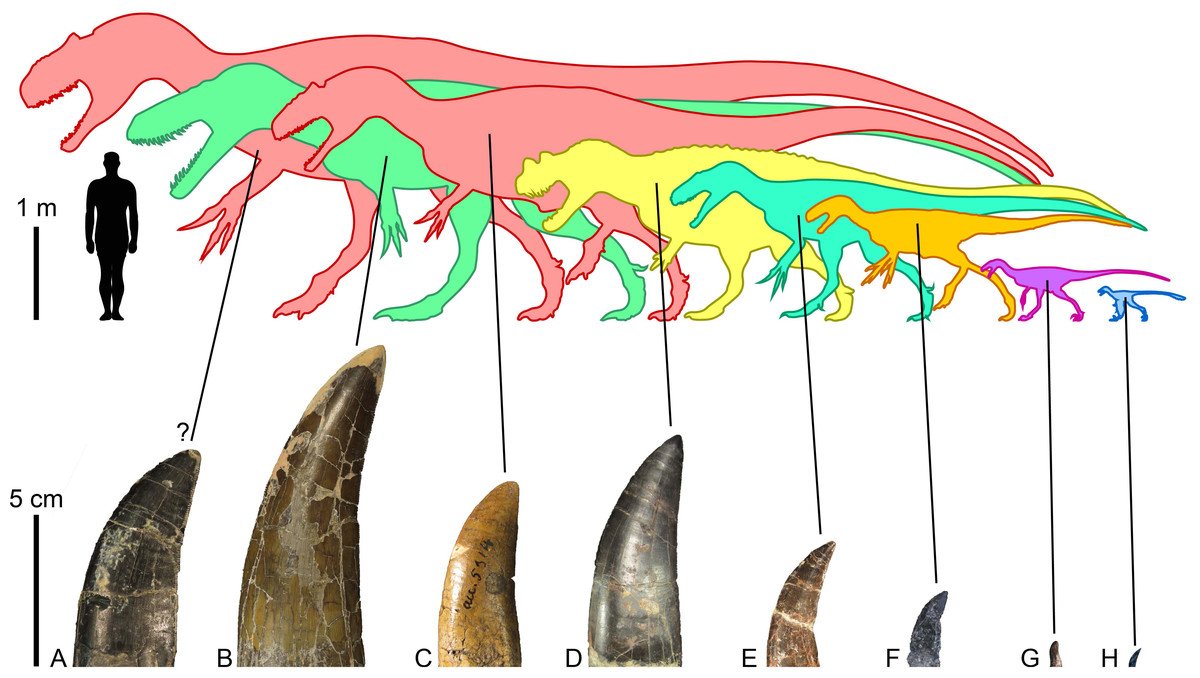

A figure showing the size of various theropods from the Morrison Formation in comparison to a human, as well as their teeth. The formation includes numerous large-bodied theropods, including Allosaurus, Ceratosaurus, and Torvosaurus, which likely would have fed upon sauropods, whether through hunting or scavenging. Lei et al., PeerJ Life & Environment 2023

Tyrannosaurs varied widely in size, although there was a general trend towards larger species over time. By the latter stages of the Cretaceous Period (around 145 to 66 million years ago), these theropods were the dominant large predators in the Northern Hemisphere, culminating in the appearance of the fearsome T. rex, which could grow up to around 40 feet in length.

In the latest study, however, the researchers investigated bite traces made by other, non-Tyrannosaur large carnivores, which have remained underreported in the scientific literature.

“It’s a really neglected area,” David Hone, an author of the study at Queen Mary University of London in the United Kingdom, told Newsweek. “We have quite a bit of work on the bites from large tyrannosaurs but not the earlier carnivorous dinosaurs and there’s generally very little on their interactions with large sauropods.”

“These herbivores were absolute giants that dominated landscapes and are very interesting and ecologically unusual. Yet we’ve done surprisingly little to try and work out what this meant for large contemporaneous carnivores.”

In the latest study, Hone and colleagues conducted an extensive survey of the scientific literature and some fossil collections cataloging bones from the “Morrison” geological formation located in the western United States.

The vast formation, which extends from Montana to New Mexico, consists of a series of sedimentary rocks deposited around 150 million years ago during the Upper Jurassic Period. It preserves the fossils of numerous dinosaur species that lived at this time.

Theropod bite marks on the limb bone of a juvenile Brontosaurus from Wyoming. Large, carnivorous theropods would likely have favored predating on young sauropods over adults, given their giant size, during the Upper Jurassic. Mathew J. Wedel, Western University of Health Sciences

No tyrannosaurs are documented in the Morrison Formation, however. Around this time in the Upper Jurassic, tyrannosaurs were mostly small animals (measuring up to around 10-13 feet in length), according to Hone. They didn’t reach larger sizes of more than 30 feet in length until roughly 125 million years ago—about 25 million years after the Morrison Formation formed.

In their survey, the researchers identified a large number (68) of sauropod bones from the formation bearing bite traces that could be attributed to feeding by non-tyrannosaur, carnivorous theropods.

The team found that bite traces on sauropod bones were abundant in the Morrison Formation (albeit less common than what would be expected in environments dominated by tyrannosaurs) and more so than previously realized.

“We were surprised to find as many bites as we did. They are clearly underreported,” Hone said.

Another of the team’s findings was that none of the observed bite traces showed any evidence of healing. This indicates that the bites occurred either in a single, lethal encounter or, more likely, are evidence of post-mortem feeding from scavenging.

The researchers also examined tooth wear in non-tyrannosaur theropods from the formation, which showed that they were biting into bones more often than previously thought—closer to the patterns seen in the large tyrannosaurs.

“It was also a surprise that there were as many bites proportionally as we found—i.e. the ratio of bitten to non-bitten bones—and that while still lower, it was getting towards the rate seen in tyrannosaurs, which are considered really good bone-biters,” Hone said.

The researchers were not able to attribute any given bite traces to specific theropods that were living at the time, such as Allosaurus and Ceratosaurus—something which remains a challenging task. But the theropods were likely toward the larger end of the spectrum.

The widespread occurrence of bite traces without signs of healing combined with the tooth wear evidence indicates that theropods were feeding on juvenile sauropods, and likely scavenging the carcasses of larger ones.

“[The study] supports what we thought was going on in terms of the general interactions between the large carnivores and the sauropods at the time, with them likely favoring predating on young sauropods and rarely tackling adults—scavenging on them when their bodies were available,” Hone said.

“Initially we thought there was a paradox with the amount of wear seen in the teeth of various theropods not matching the rate of bone bites on the sauropods. But actually this fits well with the idea that large, adult sauropods were more or less immune to predation from theropods, since the bones we are working from here are essentially all adults.”

Juvenile sauropods are very rarely found as fossils but they should have been present in huge numbers in the formation given how many eggs would be laid.

“So where are they?” Hone said. “The answer will at least partly, if not mostly, lie in the fact that they are being eaten. Theropods wouldn’t have been able to break through the skeletons of big sauropods but juveniles—anything from a hatchling to perhaps an animal of around a ton—could and would be targeted and eaten, with few bones then surviving to become fossils.”

“This new work helps us understand the ecological relationships between dinosaurs in the Jurassic,” Hone said in a press release. “It’s another important step in reconstructing the behavior of these ancient animals.”