Palaeontologists were first alerted to the fossil by a 10-year-old tourist

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e6/b0/e6b023f0-d334-43c8-9abe-4990781fed83/credit_to_oksana_vernygora_2_1.jpg)

Tourists typically visit Colombia’s Monastery of La Candelaria to explore its rich history, which stretches back to the 17th century, when Augustine monks founded the monastery. But in a flagstone of the site’s entry pathway, a hawk-eyed 10-year-old spotted a much older relic: a 90-million-year-old fish fossil that was previously unknown to researchers.

The discovery was made in 2014, but only described recently in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. As Vittoria Traverso reports for Atlas Obscura, the young tourist snapped a photo of the flagstone, and a few days later, showed it to staff at the Centro de Investigaciones Paleontologicas, a local museum.

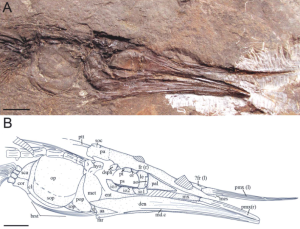

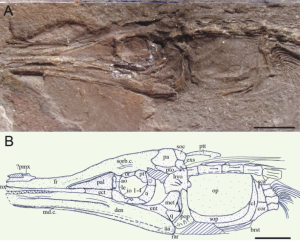

Researchers have dubbed the ancient fish Candelarhynchus padillai, which combines the monastery’s name “Candelaria” with “rhynchos,” the Greek word for nose, explains Wallis Snowdon of the BBC. Fittingly, the fish is distinguished by its pointy nose and long jaw; it looks a little like a barracuda, but the Candelarhynchus padillai has no modern relatives.

The stone that contains that fossil is roughly 90 million years old and formed during the Late Cretaceous period when much of the northern Andes was underwater. It was pulled from a nearby quarry around 15 years ago, but the fossil went unnoticed until recently, brought to light by the “inquiring mind of a child,” as Javier Luque a PhD candidate at the University of Alberta’s biological sciences department and one of the study’s authors, tells Snowdon.

According to a University of Alberta statement, the fish was preserved in “nearly perfect” condition, which is rare for fossils from the Late Cretaceous. “Deepwater fish are difficult to recover, as well as those from environments with fast flowing waters,” explains Oksana Vernygora, PhD student in the Department of Biological Sciences and lead author of the study, according to the press release.

Scientists are keen to learn more about fish fossils because they offer a unique glimpse into both the distant past and the not-too-distant future. “Often we think, we have fish now, we had fish then, we’ll likely have fish in the future,” Vernygora explains.