In the Late Jurassic, a long-necked dinosaur made a 270-degree turn while walking in present-day Colorado—and left behind a rare treat for paleontologists

:focal(2722x1815:2723x1816)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e9/4e/e94e8134-db25-4719-a364-98b1e5f2ee49/fseprd1171522.jpg)

Roughly 150 million years ago, a long-necked dinosaur tromped through present-day Colorado. At some point, the creature decided to change direction, making a wide, 270-degree turn as it walked.

Today, the sauropod’s 134 consecutive footprints—created during the Late Jurassic period—make up the largest continuous dinosaur trackway on the planet. And now, they’re federally protected for researchers and the public to access.

Last week, the United States Forest Service announced it purchased three parcels of land in Ouray County, Colorado. Two of the parcels—which together total 27 acres—encompass the 106 yards of sauropod tracks, known as the West Gold Hill Dinosaur Track site.

The footprints are located just west of Ouray, a small town in the San Juan Mountains of southwest Colorado with a population of around 1,000 residents.

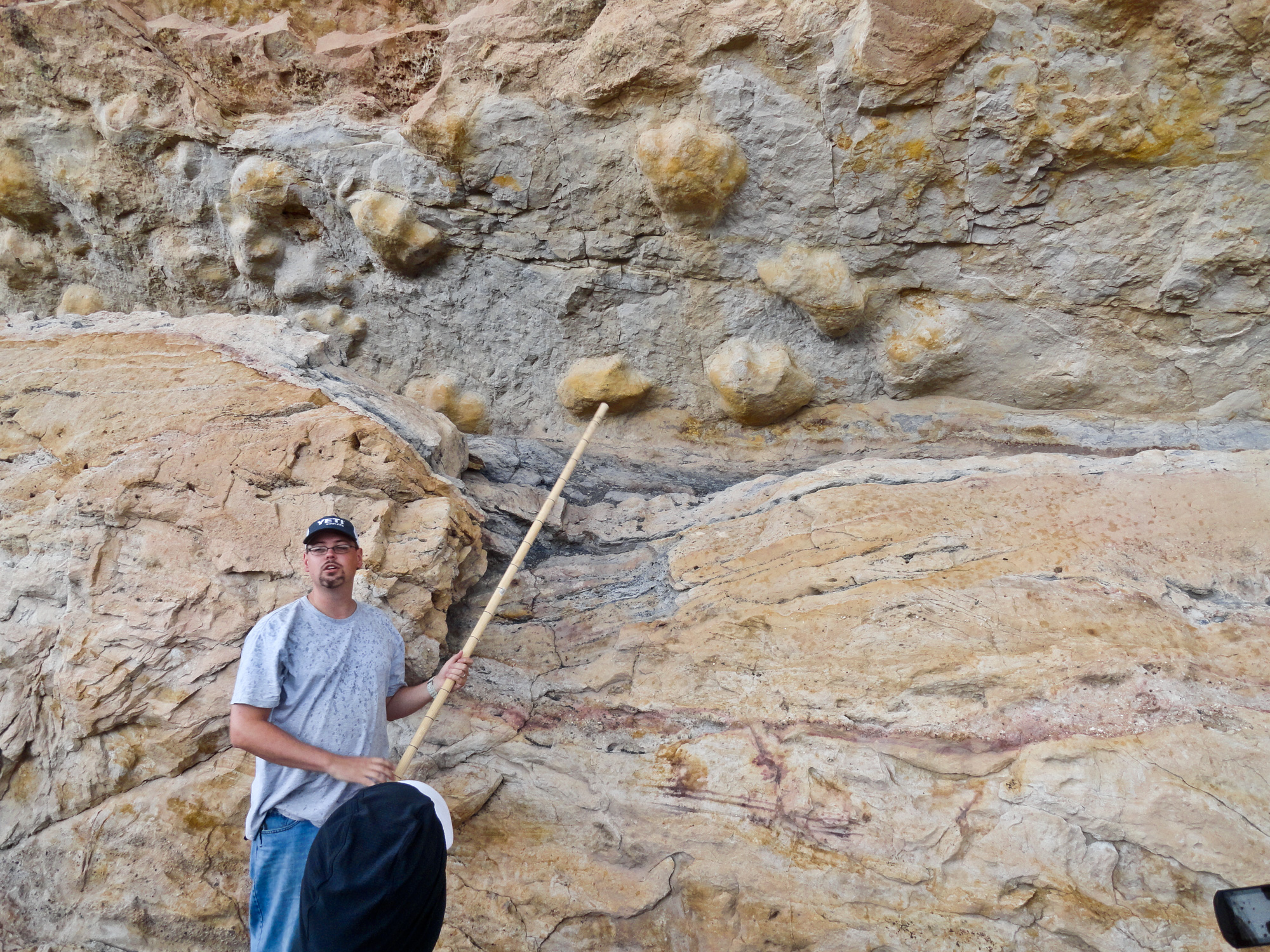

Imprinted in sandstone roughly 9,300 feet above sea level, the fossilized tracks form one of the few known examples of a dinosaur changing direction so significantly. Only five other instances have been discovered—four trackways in China and one near Moab, Utah. (The Utah site, called Copper Ridge Dinosaur Trackway, is on Bureau of Land Management land.) But this newly protected site is the only intact example of a turn greater than 180 degrees.

In 1945, the Charles family purchased the land in hopes of discovering gold. They knew about pothole-like features on the property, where they’d spent parts of their summers camping. But it wasn’t until 2021 that they realized the shallow indentations, which often filled with water, had been made by a dinosaur.

“The Charles family kids grew up thinking the strange blob-shaped impressions in the rock at their mining property above Ouray were just convenient dents holding water,” writes Erin McIntyre for the Ouray County Plaindealer. “The convenient part came from not having to haul water for their dogs, who trekked up the mountain with them each summer.”

In 2022, the family approached the Forest Service and asked if the federal agency would be interested in purchasing the land. Now, two years later, the Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre and Gunnison National Forests bought the land from the Charles Real Estate Trust for $135,000, reports the Denver Post’s Tiney Ricciardi. The agency used money from the Land and Water Conservation Fund, which was created by Congress in 1964 and is funded with oil and gas royalties.

Members of the public will be able to access the footprints along the existing Silvershield Trail, a steep, two-mile route (one way) that gains about 1,600 feet in elevation from start to finish and is open to hikers and horseback riders. Now, the Forest Service hopes to install signage and interpretive information at the site, as well as create a web page that explains the sauropod footprints’ significance.

Sauropods were a group of massive, four-legged creatures with long necks and tails. These herbivores were the largest of all dinosaurs and could grow up to about 100 feet long. At the time they roamed in what is now Colorado, the towering peaks of the Rockies (of which the San Juans are a sub-range) hadn’t been pushed up toward the sky yet.

“It’s amazing to think that, with the Rocky Mountain uplift in the later part of Mesozoic Age of dinosaurs, that dinosaur trackway layer was lifted up some 7,000 [or] 8,000 feet in elevation, and then glaciers came in few thousand years ago and scraped off all the overburden above this trackway, that somehow miraculously became preserved in sandstone to begin with,” says Bruce Schumacher, a senior paleontologist with the Forest Service, to the Denver Post. “It’s this amazing geologic story.”

:focal(2722x1815:2723x1816)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e9/4e/e94e8134-db25-4719-a364-98b1e5f2ee49/fseprd1171522.jpg)

Though the tracks were previously on private land, visitors could walk the surrounding public trails of the Uncompahgre National Forest. Over time, as parts of the tracks became exposed, people snapped photos and posted them online, but they did not reveal the exact location, according to a 2021 paper about the site. The footprints are even visible on Google Earth.

Local residents likely knew about the tracks much earlier. Rick Trujillo, one of the paper’s co-authors and a resident of the town of Ouray, “discovered [the tracks] as a youngster in the late 1950s when the track-bearing surface was mostly covered.” But he assumed they were on public land, even when he later became a geologist, per the Ouray County Plaindealer. Ultimately, Trujillo informed the Charles family of the tracks’ significance, once he learned they owned the property.

:focal(2722x1815:2723x1816)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e9/4e/e94e8134-db25-4719-a364-98b1e5f2ee49/fseprd1171522.jpg)

“The family is happy to offer this unique trackway to the U.S. Forest Service, ensuring that the land is protected and enjoyed by future generations,” says Anita McDonald, whose grandfather originally purchased the land, in the statement.