A team of paleontologists led by North Carolina State University researchers has isolated collagen peptides from the fossilized femur of Brachylophosaurus canadensis, a duck-billed dinosaur (hadrosaur) that lived what is now Montana around 80 million years ago.

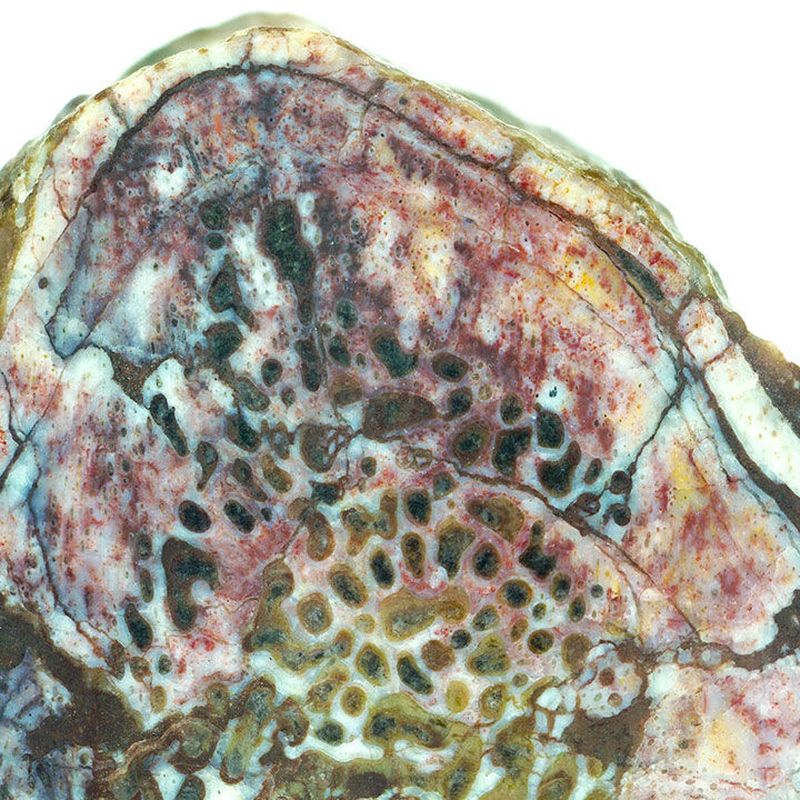

This is a Brachylophosaur canadensis fossil femur in field jacket, showing area of sampling for molecular analyses. Image credit: Mary Schweitzer.

Collagen is a protein and peptides are the building blocks of proteins.

Recovering peptides allows researchers to determine evolutionary relationships between dinosaurs and modern animals, as well as investigate other questions, such as which characteristics of collagen protein allow it to preserve over geological time.

The team, led by North Carolina State University Professor Mary Schweitzer, wanted to confirm earlier findings of original dinosaur collagen first reported in 2009 from Brachylophosaurus canadensis.

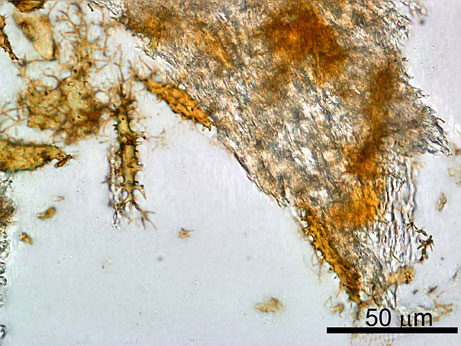

“To test the hypothesis that peptides can be repeatedly detected and validated from fossil tissues many millions of years old, we apply updated extraction methodology, high resolution mass spectrometry, and bioinformatics analyses on a Brachylophosaurus canadensis specimen from which collagen I peptides were recovered in 2009,” the authors explained.

The sample material came from the specimen’s femur, or thigh bone.

“We recovered eight peptide sequences of collagen I, two of which are identical to peptides recovered in 2009, and six of which are new,” they said.

The sequences show that the collagen I in Brachylophosaurus canadensis has similarities with collagen I in both crocodylians and birds, a result we would expect for a hadrosaur, based on predictions made from previous skeletal studies.

“Phylogenetic analyses place the recovered sequences within basal archosauria and when only the new sequences are considered, Brachylophosaurus canadensis is grouped more closely to crocodylians, but when all sequences (current and those reported in 2009) are analyzed, Brachylophosaurus canadensis is placed more closely to basal birds,” Prof. Schweitzer and co-authors said.

“The data robustly support the hypothesis of an endogenous origin for these peptides, confirm the idea that peptides can survive in specimens tens of millions of years old, and bolster the validity of the 2009 study.”

“Furthermore, the new data expand the coverage of Brachylophosaurus canadensis collagen I (a 33.6% increase in collagen I alpha 1 and 116.7% in alpha 2).”

“We are confident that the results we obtained are not contamination and that this collagen is original to the specimen,” added Dr. Elena Schroeter, lead author on the study and a researcher in the Department of Biological Sciences at North Carolina State University.

“Not only did we replicate part of the 2009 results, thanks to improved methods and technology we did it with a smaller sample and over a shorter period of time.”

“Our purpose here is to build a solid scientific foundation for other scientists to use to ask larger questions of the fossil record,” Prof. Schweitzer said.

“We’ve shown that it is possible for these molecules to preserve. Now, we can ask questions that go beyond dinosaur characteristics. For example, other researchers in other disciplines may find that asking why they preserve is important.”