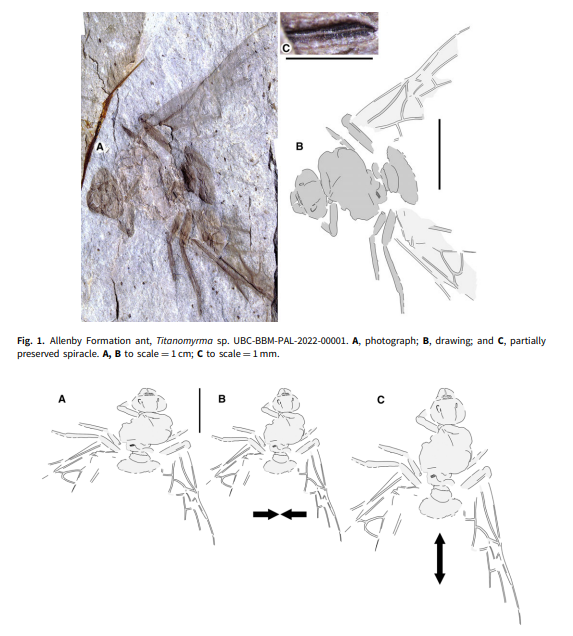

The giant fossil queen ant Titanomyrma, discovered in the Allenby Formation near Princeton, British Columbia, the first of its kind in Canada. Bruce Archibald

A Princeton resident discovered the fossil of a giant, ancient ant in the nearby Allenby Formation, a rock formation that contains many plant and animal fossils.

Researchers say it’s the first known Canadian specimen from the genus Titanomyrma, meaning “Titanic Ant.”

Scientists estimate the gargantuan insects lived around 50 million years ago and may have been about half a foot long.

The fossil extinct giant ant Titanomyrma from Wyoming that was discovered over a decade ago by SFU paleontologist Bruce Archibald and collaborators at the Denver Museum. The fossil queen ant is next to a hummingbird, showing the huge size of this titanic insect. Credit: Bruce Archibald. Bruce Archibald

Dr. Bruce Archibald is a paleoentomologist at Simon Fraser University and first discovered a similar specimen back in 2010 in Wyoming, but said he was thrilled when another fossil of the massive insect turned up in B.C.

“The tremendously big ants are mainly known from Germany and Wyoming. And so I found one of these ants in a museum drawer in the Denver Museum in about 2010 and wrote it up in 2011,” Archibald said.

“And it made quite a splash, and we figured out we were working mainly on the biogeography of this.”

Following that study, he said he and his colleagues looked at answering the next crucial question.

“How did it cross the continents and become suddenly in both places at the same time?”

Building on earlier research from 2011, the scientists found the largest ants lived in places with hot temperatures.

While Germany and Wyoming are relatively temperate now, back when these ants were around, temperatures were similar to tropical regions of today.

On top of that, Archibald says the continents were more connected back then, and would’ve allowed for more ease of access over land.

Reconstructed early Eocene northern continental positions and shorelines in polar view with Formiciinae fossil localities (G, Germany; B, Britain; W, Wyoming;T, Tennessee), and dispersal routes across the Arctic indicated by red arrows. S. B. Archibald et al

“At that time, the North Atlantic could not open by Continental movement. And so, there was continuous land from Vancouver to Frankfurt and had forests; it wasn’t that cold,” Archibald explained.

Researchers also theorized a brief period of global warming called “hyperthermals,” made it possible for the ants to travel in the higher temperatures.

This new discovery in Princeton has complicated matters since earlier theories believed an ant of such great size couldn’t survive in what is now interior B.C.

the new Canadian fossil was distorted by geological pressure during fossilization, so its true life size is unclear. The fossil can be compressed or lengthened resulting in a size difference which scientists are looking into. Archibald et al. / The Canadian Entomologist

Dr. Archibald says researchers may need to revise their ideas of climate tolerance of giant ants if the specimen is, in fact, of comparable size to other specimens previously found.

“So if it’s a small ant, then we were probably pretty much right in our 2011 idea, and these ants needed to reduce themselves in size, in order to live in a cooler climate. If it’s a big and we were wrong, we’ve got to revise what we think about the ecology of these giant ants. Then maybe they could across the north cross the Arctic at any time and they’re not heat loving at all. Maybe they’re just winter hating”

For more information on this study, Dr. Archibald is also hosting a talk at the Beaty Biodiversity Museum at UBC on March 16th at 6 p.m.

The talk will cover fossilized insects around B.C. and what they can do to inform people about global biodiversity.