Damage to the armoured fossil of an ankylosaur suggests injuries from another ankylosaur

It’s a picture we thought we understood. Ankylosaurs, tank-like armoured dinosaurs possessed an intimidating weapon — a powerful muscular tail tipped with a massive bony club. It used that tail to defend itself against terrifying predators like Tyrannosaurus rex, dealing mighty blows against the huge carnivores.

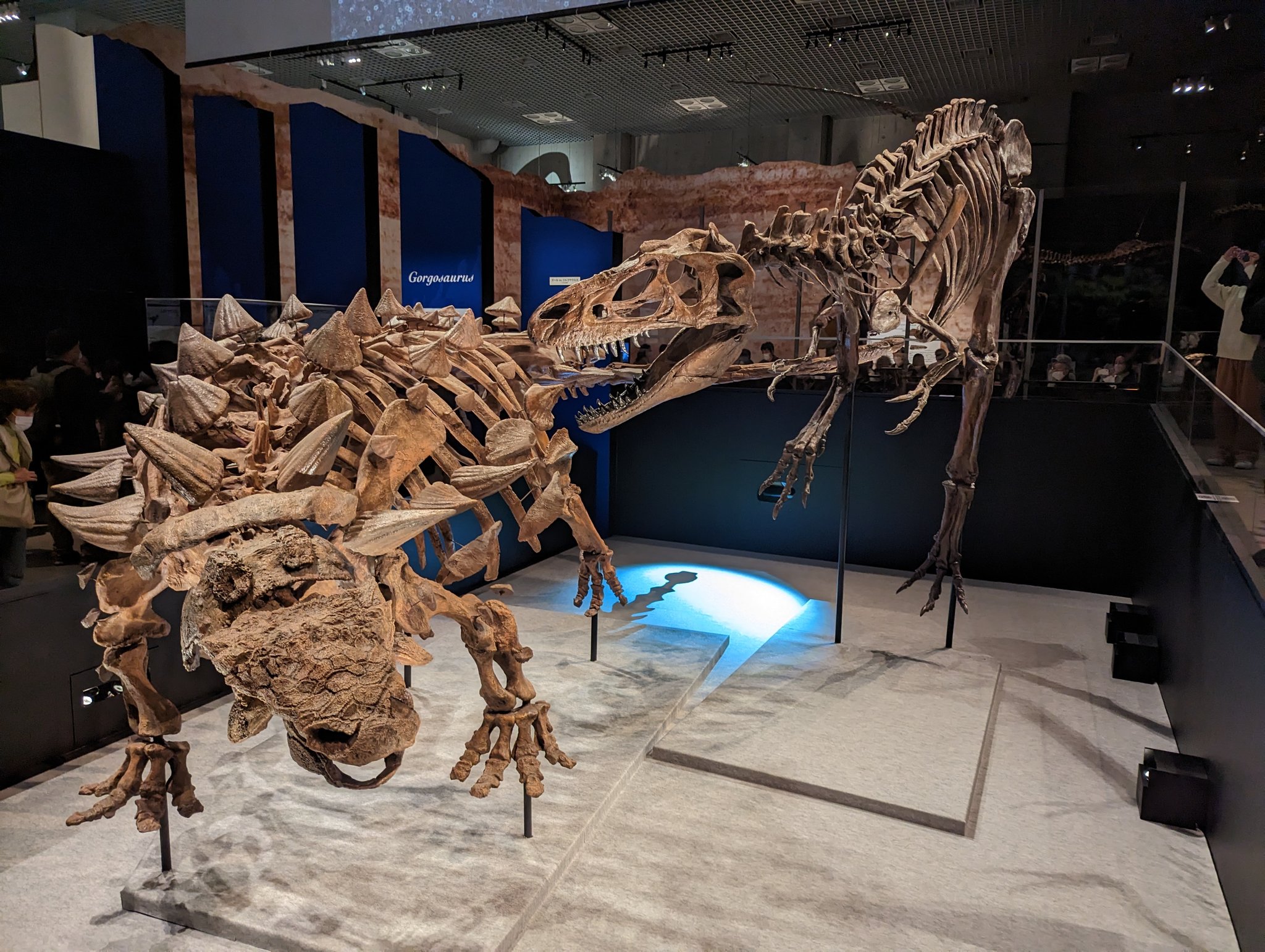

But a new study of one of the best preserved ankylosaurs ever discovered, an animal known as Zuul crurivastator,housed at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, is telling a different story. Ankylosaurs might have developed their weapon to fight each other in violent battles over mates or territory.

Paleontologist Victoria Arbour, of the Royal BC Museum in Victoria, has been studying the fossil since its discovery, and was part of the team responsible for naming the species. The first part of the name, Zuul, came from the similarity between the fossil’s head and the demon Zuul in the original Ghostbusters movie. The second part of its name translates to “destroyer of shins,” reflecting what they imagined the ankylosaur’s mighty tail could do to the legs of T.rex or another predator.

But the new study of Zuul’s remains gives support to a suspicion Arbour had been cultivating for some time — that ankylosaurs mostly tangled with each other, rather than predators.

Arbour’s team published their work in Biology Letters.

“Herbivorous animals often don’t really fight predators unless it’s like the very last resort to not getting eaten,” she said in an interview with Quirks & Quarks host Bob McDonald.

“But lots of herbivorous animals fight each other for mates and territory. So if you think about things like bighorn sheep or deer, they’ve got these weapons on their heads and they really use those for fighting each other, usually at mating time.”

During initial study, important parts of Zuul’s body weren’t visible, as they were still encased in more than 30 tonnes of rock. But as that rock was removed at the museum, evidence of Zuul-on-Zuul violence appeared, said Arbour

“We saw that some of the very big triangular spikes along the flanks actually we’re missing tips and the tips had sort of healed and grown back into a sort of new shape.”

These hand-sized bony spikes were part of Zuul’s armour, but the damage to them wasn’t consistent with the tearing bites of a predator’s sharp teeth. They looked more like the result of a blunt force strike with a large heavy object. And the fact that the damage was on the animal’s flanks was also significant.

“Based on where those broken spikes are found, we think that that’s more consistent with it having been inflicted by another Zuul.”

Paleontologist Micheal Ryan from Carleton University, who wasn’t involved in the study, thinks that’s a reasonable conclusion to draw. “I see that as being more typical of the interspecific interaction between two ankylosaurs than I do with a large theropod attacking.”

These tail whipping battles could have been extremely violent, and Zuul might have gotten off easy in its fights, with damage only to its armour.

“We also know that from some other ankylosaurs, there are examples of broken ribs,” said Arbour. “Certainly ankylosaurs could swing their tails with enough force to break bone and really cause some major damage to whoever they were hitting them with.”

Nevertheless, Zuul’s tail-fighting strategy might have an advantage over that of modern herbivores who use antlers or horns on their heads in fights, said Arbour.

“Your head is where your brain and your eyes and your mouth, all these important parts of your body for survival are located. So maybe in some ways having your weapon on your tail is actually a little bit of a better idea, because if you break your tail, at least you can keep going about your day.”

Some dinosaurs likely did use their heads for this type of competition, though. Micheal Ryan’s specialty is horned dinosaurs like Triceratops, which had three horns projecting from its face. Fossils of horned dinosaurs have been found with scrapes and even punctures on the bony shields that surrounded their heads.

“Those horns were slipping across each other’s shields and sometimes one of them would have punctured through,” said Ryan. “And again, the analogy with modern herbivores and the fact that you know things like the horns of bighorn sheep, or the antlers and horns of of moose and deer and stuff evolved essentially for intraspecific [within species] conflict.”

What the fossil doesn’t tell is why Zuul might have been fighting another ankylosaur. Arbour points out that he most spectacular battles in modern herbivores are often between males over mates. Think of bighorn sheep butting heads, or moose or deer wrestling with their antlers. But there’s no reason to assume this was the case with dinosaurs — perhaps the females fought over mates or territory 75 million years ago. And in any case Arbour says they haven’t been able to determine Zuul’s sex.

What Arbour has more confidence in is that the picture these findings support changes the focus on what fights were really important in the life of ankylosaurs, and takes the focus off the kill-or-be-killed picture we have of dinosaur life. “The whole reason that tail clubs evolved probably wasn’t necessarily as an anti-predator defence, but really more for fighting within their own species.”