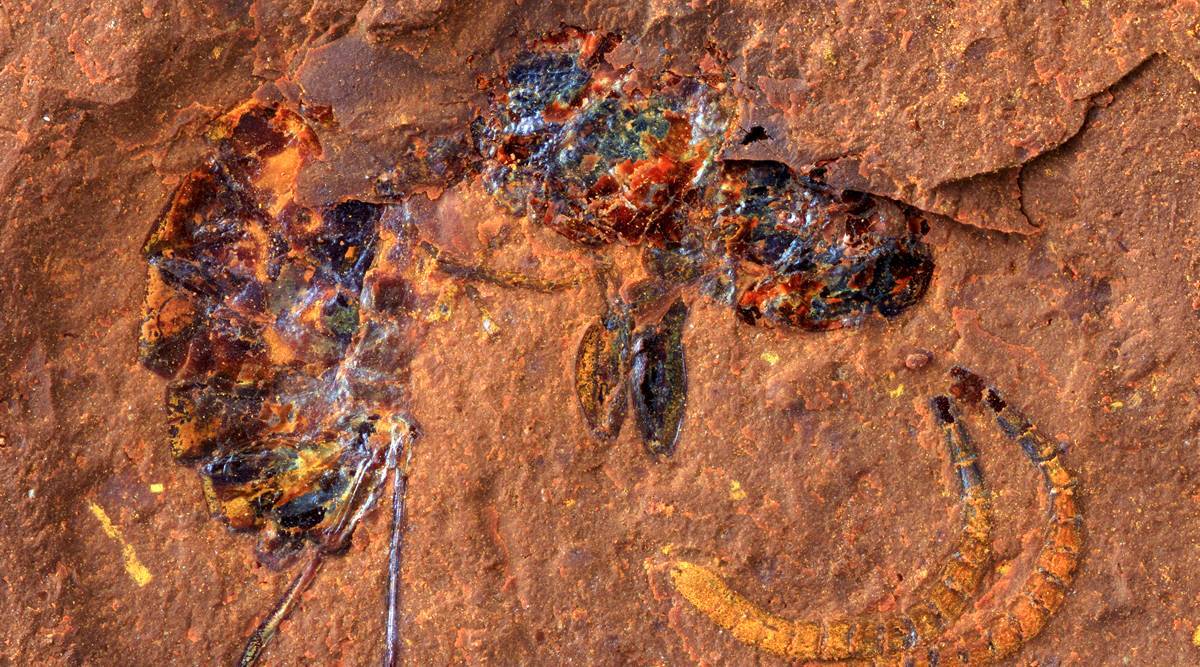

Photograph of a pharate caddisfly from the McGraths Flat fossil site. Pharate insects are fully developed adults that have not yet left the pupal cuticle and expanded their wings. Credit: Michael Frese

About 11 to 16 million years ago, in the middle of the Miocene period, more than 100 caddisflies met their end in a lake.

Over time, the iron-rich sediments at the bottom of the lake formed a thick layer of the mineral goethite. Along with many other animals, the caddisflies became fossilized in a Konservat-Lagerstätte, a name given to a fossil site that preserves extremely fine details. The site is named McGraths Flat and is located in central New South Wales.

The caddisflies are so well preserved that the nanostructure of their eyes could inspire new products. These could range from antimicrobial paints to sunglasses that repel water.

Fossilized fossil eyes

Caddisflies are small, moth-like insects with hairy wings. They are an order of insects known to scientists as Trichoptera. Fly fishers call them sedges.

Caddisflies spend most of their lives as aquatic larvae. They also pupate underwater.

_16x9.jpg)

The caddisflies preserved at McGraths Flat died as larvae and pharate adults. Pharate adults are pupae that have completed metamorphosis but have not yet broken free of their pupal cuticle. This cling-wrap like covering protects them until they fly free from the water’s surface.

Dr. Michael Frese is a visiting scientist who worked with Dr. Alice Wells at our Australian National Insect Collection and Matthew McCurry from the Australian Museum. Together, they studied the caddisflies at McGraths Flat.

“Using a scanning electron microscope, we could see details of the caddisflies’ compound eyes, silk glands, mouthparts, gastrointestinal tract, claws and genitalia. We even found pollen inside the gut of one caddisfly,” Michael said.

“Most remarkable were two fossils that showed the corneal nanocoating. This is the molecular structure on the surface of the caddisflies’ compound eyes.

“We think these might be among the best-preserved fossilized eyes on the planet.”

Michael said the nanocoating suggests the eyes were anti-reflective, perhaps because the caddisflies were adapted to low light.

“The surface was super hydrophobic, both chemically because it was a mixture of protein and wax, and also structurally. Its pattern might inspire new coatings for glass windscreens or sunglasses,” he said.

“The surface is also anti-bacterial because it stresses the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. It could inspire paint to make hospital walls resistant to bacterial growth.”

Michael said that he has seen a similar coating on the wings of a fossil cicada from the same site. The cicadas from the site are the only fossil cicadas from Australia. They are also by far the biggest cicada fossils on the planet.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) image showing the highly regular hexagonal pattern of the corneal nanocoating on the eyes of a pharate caddisfly. Credit: Michael Frese