A pair of amateur paleontologists have recently uncovered a world-class fossil site containing the remains of creatures that lived around 470 million years ago.

The site, which contains almost 400 exceptionally well-preserved fossils, is located in the Montagne Noire mountain range in the south of France’s Hérault department. The results of the first analysis of the site have now been published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

The analysis of the fossil site, known as the Cabrières Biota, was conducted by an international team of researchers, including scientists from the Faculty of Geosciences and Environment at the University of Lausanne (UNIL) in Switzerland, in collaboration with the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS).

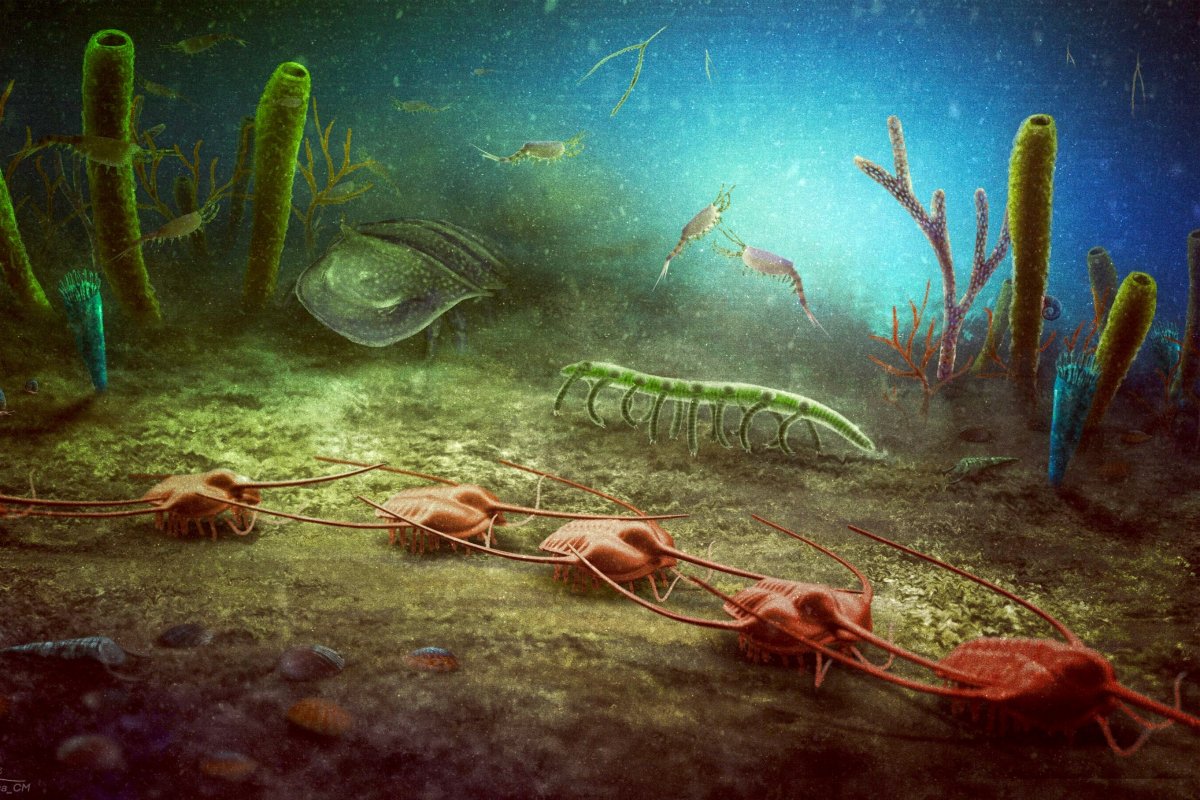

The rich and diverse fossil site preserves organisms living in what was a marine ecosystem hundreds of millions of years ago. The biota contains a variety of different remains—including shelly components, as well as extremely rare soft elements, such as digestive systems and cuticles—in a remarkable state of preservation.

![400 Well-Preserved Fossils Unearthed in a Mountain Range in France [Study] 400 Well-Preserved Fossils Unearthed in a Mountain Range in France [Study]](https://1721181113.rsc.cdn77.org/data/images/full/51904/400-well-preserved-fossils-unearthed-in-a-mountain-range-in-france-study.png?w=820)

“Soft-bodied fossil sites are always exciting—they are globally rare and are a critical part of being able to understand ancient ecosystems,” Jonathan Antcliffe, an author of the study with UNIL, told Newsweek.

Intriguingly, the area in which the Cabrières Biota lies was located very close to the South Pole when these organisms were alive, revealing the composition of the southernmost ecosystems on Earth during the Early Ordovician period (around 485 million to 470 million years ago).

According to researchers, the site is of worldwide importance, providing unprecedented insights into such polar ecosystems in the Early Ordovician.

“We’ve been prospecting and searching for fossils since the age of twenty,” Eric Monceret, one of the amateurs who discovered the site, said in a press release.

“When we came across this amazing biota, we understood the importance of the discovery and went from amazement to excitement,” Sylvie Monceret-Goujon, the other amateur, said in the release.

The first analysis of the biota has revealed the presence of arthropods—an extremely diverse group of animals that have a hard shell known as an exoskeleton. This group includes arachnids, insects and crustaceans, among many others. These creatures must go through stages of molting to keep growing, during which they shed their old exoskeleton to reveal a new one.

The researchers also identified cnidarians in the biota, a group that includes jellyfish and corals, as well as a large number of algae and sponges.

“Particularly the preservation of the sponges—which are very delicate and usually fall apart on death—and algae are very remarkable,” Antcliffe said.

The high biodiversity of the site indicates that the area served as a refuge for species escaping the high temperatures present further north around 470 million years ago, according to the researchers.

“At this time of intense global warming, animals were indeed living in high latitude refugia, escaping extreme equatorial temperatures,” UNIL researcher Farid Saleh, the first author of the study, said in the release.

The first analysis of the site marks the beginning of a long research program involving large-scale excavations and in-depth fossil analyses. Over the course of this program, scientists are hoping to uncover more information about the anatomy of the preserved remains, as well as to determine their evolutionary relationships and shed light on their behavior when they were alive.