Gathering intelligence on foreign nations was no easy task for America in the 1960s.

Spy planes like the U-2 captured high-resolution imagery but ran the risk of provoking foreign governments and being shot down. Photo reconnaissance satellites were safe from antiaircraft missiles and less provocative than overflights, but they produced lower-quality imagery and were slow to transmit data to photo interpreters.

Enter the Manned Orbiting Laboratory.

The program aimed to expand the US military’s capabilities to surveil foreign adversaries at a time of high geopolitical tensions by marrying the two reconnaissance methods: operating a crewed spy satellite in space.

Manned space operations

The Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) was a joint project between the US Air Force and the National Reconnaissance Office and prompted by the need for rapid and reliable intelligence following the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 and during the Cold War and the Vietnam War.

Then-US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara publicly unveiled the program in December 1963, and President Lyndon B. Johnson formally approved the project in August 1965. Though the program was intended to give the US military a reconnaissance vantage point in space, it was portrayed as an operation to find what humans are capable of in space.

“This program will bring us new knowledge about what man is able to do in space,” Johnson said at the time. “It will enable us to relate that ability to the defense of America. It will develop technology and equipment which will help advance manned and unmanned space flights. And it will make it possible to perform their new and rewarding experiments.”

Operations on the MOL began in the spring of 1964. The MOL sought to obtain high-resolution photographic imagery of foreign adversaries like the Soviet Union. While satellites effectively gathered intelligence, they faced limitations like cloud cover and time delays in retrieval that prevented them from consistently taking useful photographic imagery. An operator onboard the satellite would allow them to circumvent those issues and identify where and when to capture an image in real-time.

![Alternate History] First Crewed Manned Orbiting Laboratory Flight, MOL 3 (December 15, 1969) : r/KerbalSpaceProgram](https://preview.redd.it/8oqjho3a4b651.png?auto=webp&s=a3dd31a599c741a49254565a95a26dbc25f5185d)

“The idea was humans could help pick targets in real time, they could identify cloud cover and save film,” Richard Truly, a former MOL crewmember, said in 2022. “The system was resource-limited because it was a film system, not electronic like we have now. But the whole idea was to have a far more capable intelligence capability because you had people there that could think and act and take action in real time during the flight.”

A 60-foot-long space station

The MOL program originally planned to have six launches with a flight duration of two to four weeks — an ambitious feat given that the longest a human had been in space previously was eight days during NASA’s Gemini V mission in 1965.

A two-man crew would lift off in a modified Gemini capsule atop a spacecraft that would house the MOL. After the flight duration, the capsule would detach and return to Earth while the MOL would remain in orbit.

Proposed configuration

The proposed configuration of the MOL was that the front of the spacecraft would house the transfer tunnel and fuel cells, behind that would be the laboratory divided into work and living compartments, and the rear of the spacecraft would be the equipment module and breathing tanks.

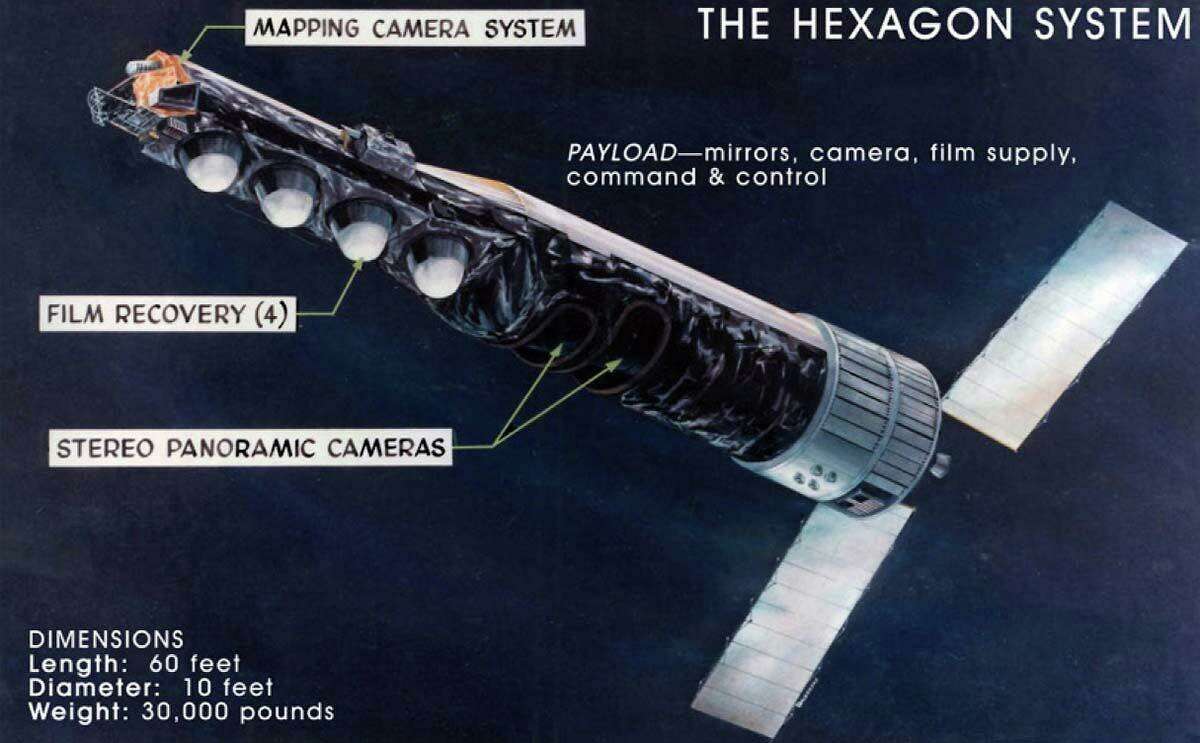

Aside from the laboratory where astronauts would conduct experiments, the primary payload of the MOL would be a telescope used for military reconnaissance.

The telescope was designed to have a primary mirror that was 72 inches in diameter, and its imaging system was codenamed Dorian.

Astronaut selection

After three rounds, the US Air Force selected 17 pilots to participate in the MOL program.

One of the pilots, Robert H. Lawrence, was the first African American selected to be an astronaut by any national space program. Lawrence was among the final selection group completed in June 1967, but he died in an F-104 Starfighter crash in late 1967.

Astronaut training

MOL crewmembers had a busy training regiment to prepare for various unexpected events while in space. They were given survival training to prepare for unexpected deorbiting in the case of spacecraft leaks.

Crewmembers also trained in spacecraft simulators and went through underwater training at the Navy dive school in Key West, Florida.

Most importantly, they received training with the National Photographic Interpretation Center to learn more about photographic intelligence and subject recognition — a central part of the MOL’s program objective.

No spacewalk needed

The external design for the MOL’s spacecraft was similar to that of NASA’s Gemini. But the major difference was that a hatch cut into the heat shield allowed astronauts to pass between the capsule at the front of the spacecraft to the laboratory and living quarters in the back without a spacewalk.

Narrow passageways

Astronauts required a special spacesuit that was flexible enough to allow them to crawl through the narrow passageway between the Gemini capsule and the laboratory on the MOL.

Special spacesuits

Though the spacesuit never actually made it into space, NASA used the technology behind it in future spacesuit development.

Experiments and reconnaissance

While the existence of the MOL was publicly known, its mission to gather photographic intelligence on foreign adversaries was highly classified. However, press coverage at the time conveyed the MOL as a reconnaissance mission, and the top secret classification of the program prevented officials from denying the claims.

Amid concerns about how other countries would react to the US military operating in space, Louis Mazza, Chief Program Security officer of the NRO, proposed to “admit we have a DOD manned orbital laboratory, and its mission is to determine man’s potential usefulness in space.”

Thus, MOL operations expanded to include 10 experiments called Project Manifold, which studied cell growth and new technologies aboard the spacecraft.