The fossil is positioned in a way that suggests the entire skeleton may be preserved within the hill.

Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology/PA NewsThe dinosaur’s fossilized skin may be able to help scientists determine what hadrosaurs really looked like.

A newly-discovered fossil, researchers say, could be an incredibly rare discovery: a complete hadrosaur skeleton.

According to The National, the exposed fossil of the large, plant-eating, duck-billed species was found sticking out of a hillside at Dinosaur Provincial Park in Alberta, Canada.

At the moment, all that’s visible of the fossil is a portion of the dinosaur’s tail and right hind leg, but researchers Brian Pickles of the University of Reading and Caleb Brown from the Royal Tyrrell Museum explained that the way in which the fossil is arranged suggests the skeleton is in a sitting position — and may be fully preserved within the hill.

“This is a very exciting discovery, and we hope to complete the excavation over the next two field seasons,” Pickles said. “Based on the small size of the tail and foot, this is likely to be a juvenile. Although adult duck-billed dinosaurs are well represented in the fossil record, younger animals are far less common. This means the find could help paleontologists to understand how hadrosaurs grew and developed.”

Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology/PA NewsA close-up of the hadrosaur’s fossilized skin.

Most dinosaur bones found in museums are models of fossils found in the field based on what researchers have been able to piece together, but the discovery of a fully-intact skeleton could provide scientists with crucial knowledge in understanding not just how these dinosaurs looked, but how they developed.

“Hadrosaur fossils are relatively common in this part of the world, but another thing that makes this find unique is the fact that large areas of the exposed skeleton are covered in fossilized skin,” Brown said. “This suggests that there may be even more preserved skin within the rock, which can give us further insight into what the hadrosaur looked like.”

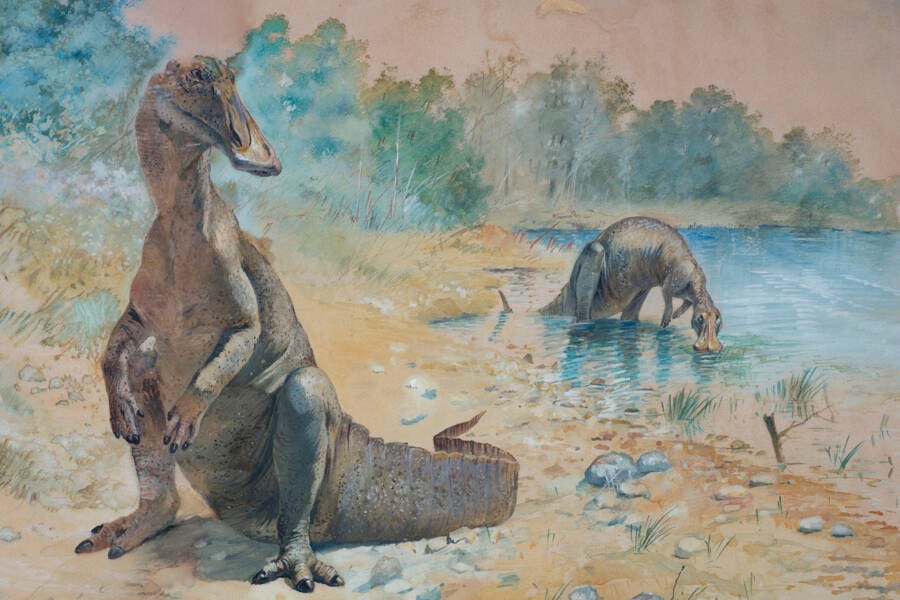

Per Daily Mail, hadrosaurs are known as “duck-billed” due to the large, flat, bill-like appearance in the bones of their snouts. The name hadrosaur itself stems from the ancient Greek for “stout lizard.”

They were large herbivores, living during the Late Cretaceous Period between 65 and 75 million years ago, ranging from roughly 23 to 26 feet in height, and weighing between two and four tons.

Public DomainAn illustration depicting what researchers believe some hadrosaurs looked like.

Pickles and his team initially came across the fossils during a field school scouting trip in 2021 when a volunteer crew member named Teri Kaskie noticed a small bit of the skeleton jutting out from the hillside.

“I instantly went up to Brian and [said] you need to come to take a look at this! And as it turned out, it was something really cool,” Kaskie told CBC.

Now, the first international paleontology field school, composed of academics and students from the University of Reading and the University of New England in Australia, is working in collaboration with the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Canada to excavate and preserve the exposed fossil.

According to Brown, roughly 400 to 500 dinosaur bones have been excavated from the area — but finding any fossils with skin is quite rare. Even rarer is finding a dinosaur preserved in the same position as they were in life.

“When you find skin, or even better, internal organs, you can start to look at how these animals were when they were living and breathing,” Pickles said.

“Dinosaur Provincial Park is kind of the crown jewel of that,” said Brown. “There’s no other place in the world that has the same abundance of dinosaur fossils and the same diversity of dinosaur fossils in a very small area.”

Due to the size of the specimen, it’s likely going to take several months to fully excavate the skeleton — possibly, as Pickles said, over two field seasons. After the excavation is complete, the fossil will be transported to the Royal Tyrrell Museum’s Preparation Lab where a team of technicians will work to identify and uncover the creature.

As they prepare the fossil, they will be able to determine whether the entire skeleton is there, how well-preserved it is, and how much of the animal’s skin remains. In order to identify the precise species of hadrosaur, however, researchers will need its skull.

The process, they said, will likely take several years based on the creature’s size and level of preservation.

“I plan to follow this dinosaur through until it’s a specimen on display in the Royal Tyrrell Museum,” Pickles said.