“According to our calculations, the planet will crash into the star in just 3 million years.”

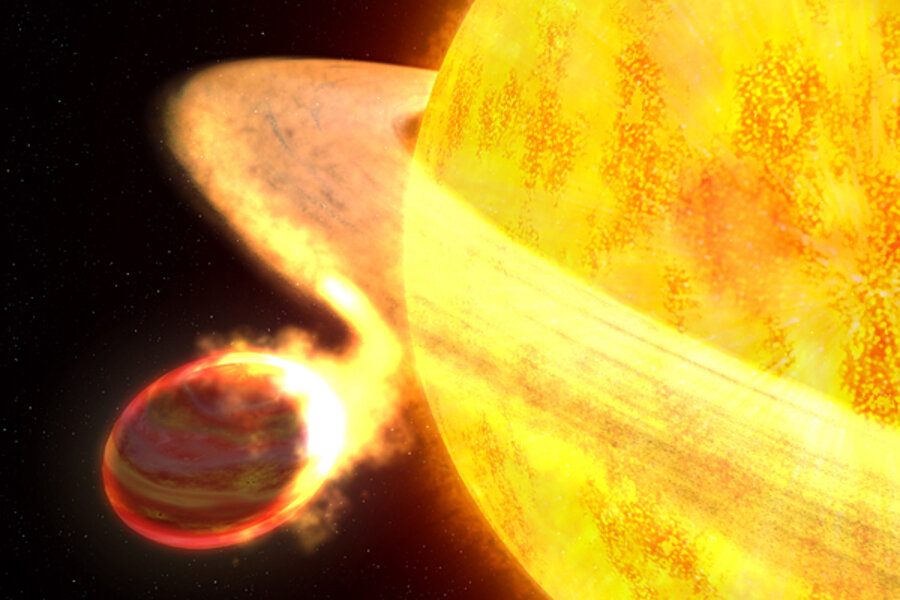

An illustration shows the egg-shaped planet WASP-12b on a death spiral towar its yellow dwarf parent star (Image credit: Robert Lea)

Astronomers have discovered that a distant, scorching hot planet twice the size of Jupiter is on a death-spiral trajectory that will send it careening into its parent star. A crash is expected to happen relatively soon, cosmically speaking.

In other words, this may seem like an incredibly long time, but the fact that stars like the sun live for around 10 billion years means it is a very (very) short period on cosmic scales.

WASP-12b gets too close for comfort

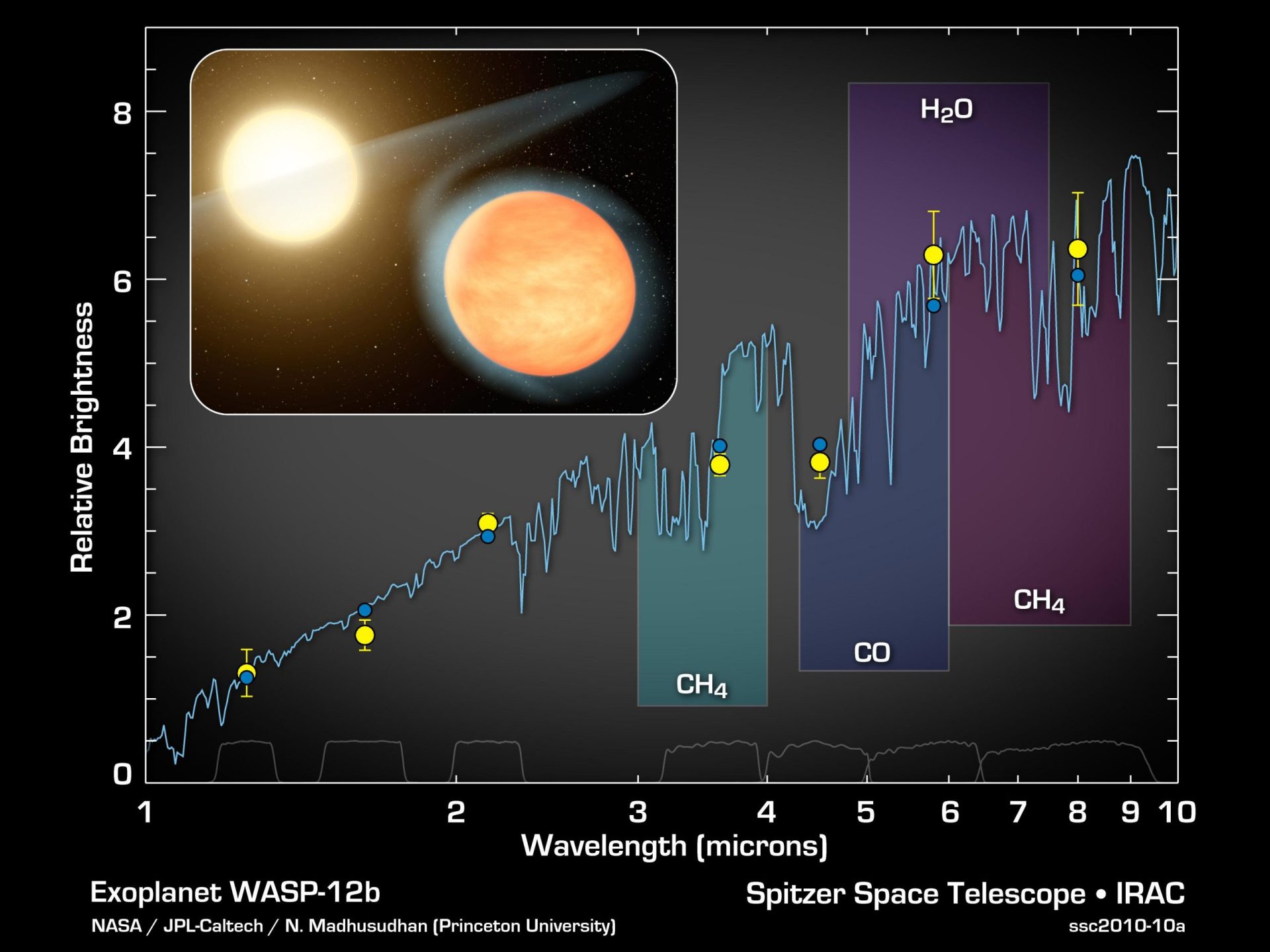

In general, the doomed planet WASP-12b orbits its yellow dwarf star so closely that it almost fits an entire year into a single Earth day. This proximity classifies WASP-12b as an “ultra-hot Jupiter” planet, a name that is fitting considering radiation from this star ceaselessly belts the planet, giving it a surface temperature of around 4,000 degrees Fahrenheit (2,210 degrees Celsius).

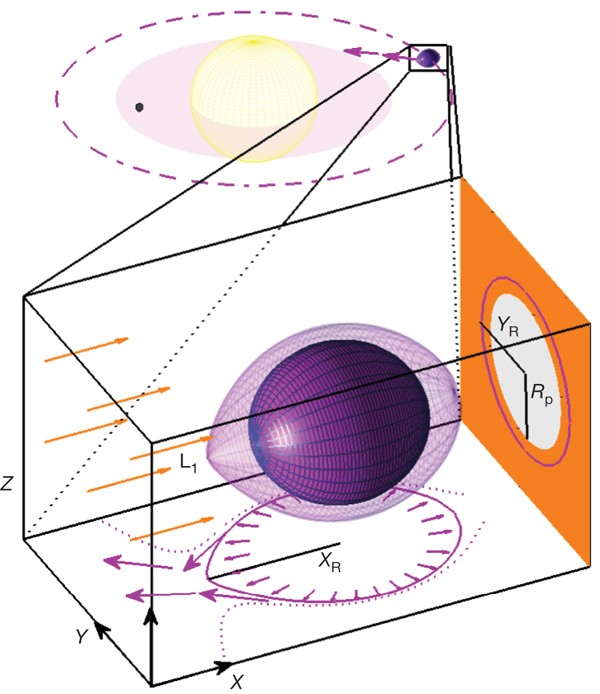

That isn’t the only thing, however, that makes this doomed world an extreme exoplanet unlike anything found in the solar system. The immense gravity felt by WASP-12b at just 2.1 million miles from its star generates such great tidal forces that it is now shaped like an egg.

This gravitational influence also strips material from WASP-12b, which forms a disk of matter around the planet’s yellow star.

When it was discovered in 2008, WASP-12b was the hottest planet ever seen, a record it surrendered in 2018 to another world dubbed Kelt-9b. At the time, WASP-12b was also the closest planet to its star, though that record is now held by K2-137b, which sits just over half a million miles from its red dwarf star that’s located some 322 light-years away from Earth.

One surprise that the team’s analysis delivered was some evidence that suggests the dwarf star had already come to the end of its main-sequence lifetime, a period that sees stars burning hydrogen in their cores.

Leonardi thinks that the findings regarding the doomed status of WASP-12b could indicate that other ultra-hot Jupiters could also be on collision courses with their stars.

“We still have to figure out if what we observed is a unique scenario or a common event in the universe,” Leonardi said. “According to some population studies, the number of hot Jupiters orbiting very close to their stars decreases when we observe older stars, so this could be an indication that many planets experience tidal decay and crash into their stars.”

Leonardi added that he is now working with the team behind the European Space Agency (ESA) mission CHaracterising ExOPlanet Satellite (CHEOPS) to determine the orbital decay rate of other hot Jupiters.

“This study is just the beginning of a long search for orbital decay,” he concluded.