Dinosaur Feather and Tick Preserved in Ancient Amber Prove Parasitic Blood Suckers Feasted on Prehistoric Animals

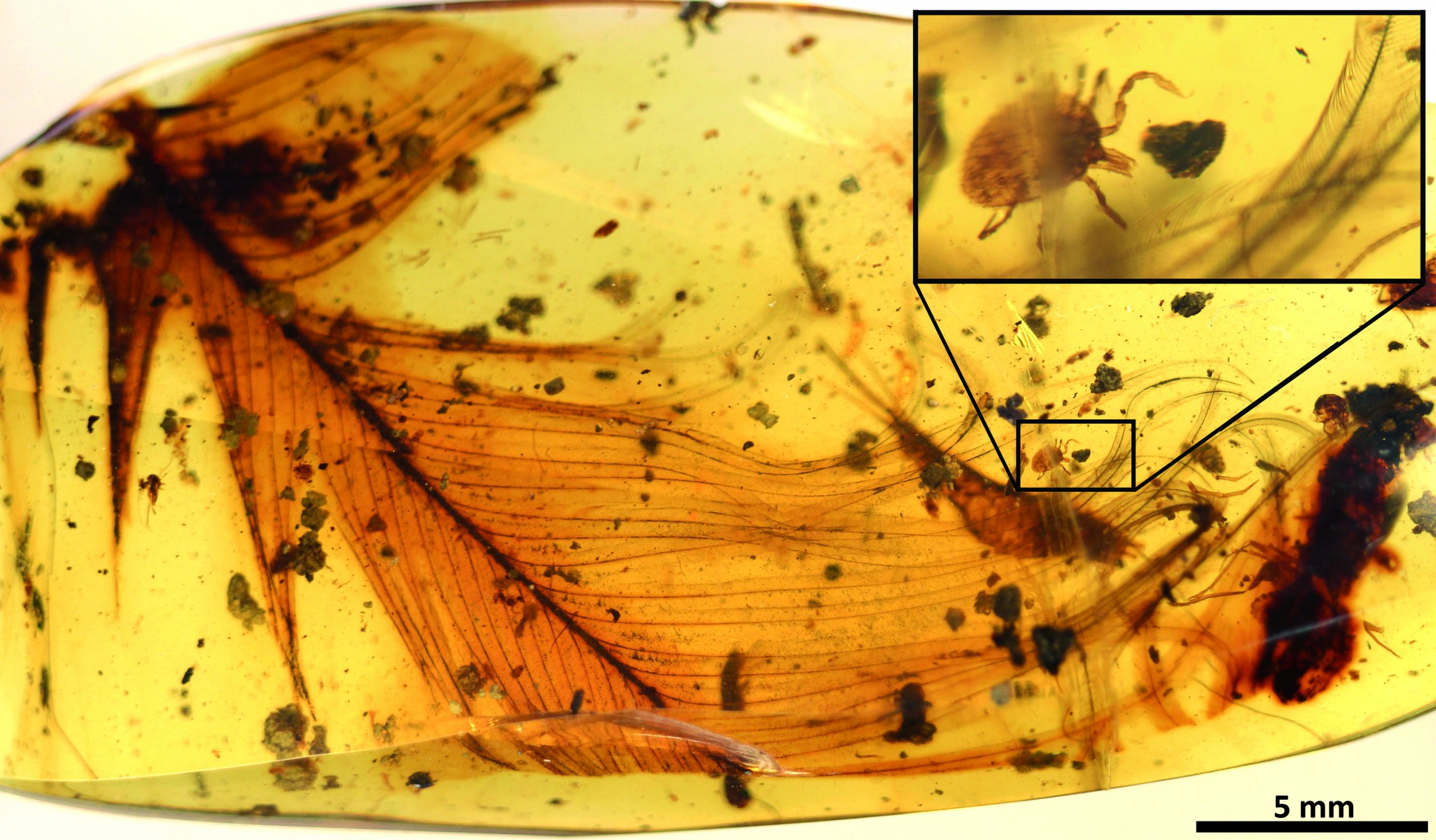

At some time during the Cretaceous era, a tick crawled onto a dinosaur feather, looking for its next meal. But somehow the tick and the feather both became encased in amber. Both specimens stayed like that, frozen in time for nearly 100 million years, only to be discovered in 2017. Now, this tiny bit of tree resin serves as the first direct proof that ticks fed on dinosaurs.

An American fossil and gem collector donated several samples of 99-million-year-old amber to the American Museum of Natural History, in New York, that contained ancient ticks. An international team of scientists analyzed the tiny insects inside. They found the oldest-known example of a blood-sucking parasite directly on the remains of their host; in this case, a dinosaur feather.

These ticks are the first specimens of a newly described genus, called Deinocroton, and species, called Deinocroton draculi, or “Dracula’s terrible tick.” The research was published in the journal Nature Communications.

“Ticks are infamous blood-sucking, parasitic organisms, having a tremendous impact on the health of humans, livestock, pets, and even wildlife, but until now clear evidence of their role in deep time has been lacking,” said Enrique Peñalver from the Spanish Geological Survey, according to the press release.

The international team of scientists who wrote the paper knew that the feather was from a dinosaur and not a modern bird because it’s from the Cretaceousera which was 145-66 million years ago, before modern avians had evolved. This specimen is not the first example of dinosaur feathers, or even an entire portion of a dinosaur tail, found in amber. However, these discoveries are still quite rare, and this one represents the first evidence of a blood-sucking parasite having targeted dinosaurs.

Some of the ticks that the paleontologists found in the amber were engorged, meaning that their bodies were swollen with blood, just like modern ticks when they’ve buried their heads in hosts. That engorged state could have raised hopes among movie fans that the ticks held dinosaur blood, just like the mosquitos in Jurassic Park that were so pivotal to the plot.

However, unlike in the Michael Crichton novel and subsequent Hollywood film franchise, this real life discovery has no chance of containing blood that could be extracted in order to clone a dinosaur. All attempts to extract DNA from ancient amber-coated insects have failed, including an attempt on bees in 2013.

DNA is an unstable molecule, and it breaks down too quickly to use ancient specimens for cloning. In an interview with LiveScience, de-extinction expert and associate professor of evolutionary biology at UC Santa Cruz Beth Shapiro explained that enzymes, radiation, oxygen, and water all alter DNA beyond recognition over time. The process of DNA degradation starts shortly after death. In the case of the ticks, scientists aren’t even certain that the blood inside the engorged one is dinosaur, because part of the animal did not become encased in amber and the contents of its body were exposed to regular decomposition. This made the possibility of sequencing just part of the DNA even less likely.

Still, this discover may be the closest to Jurassic Park we’ve ever been.